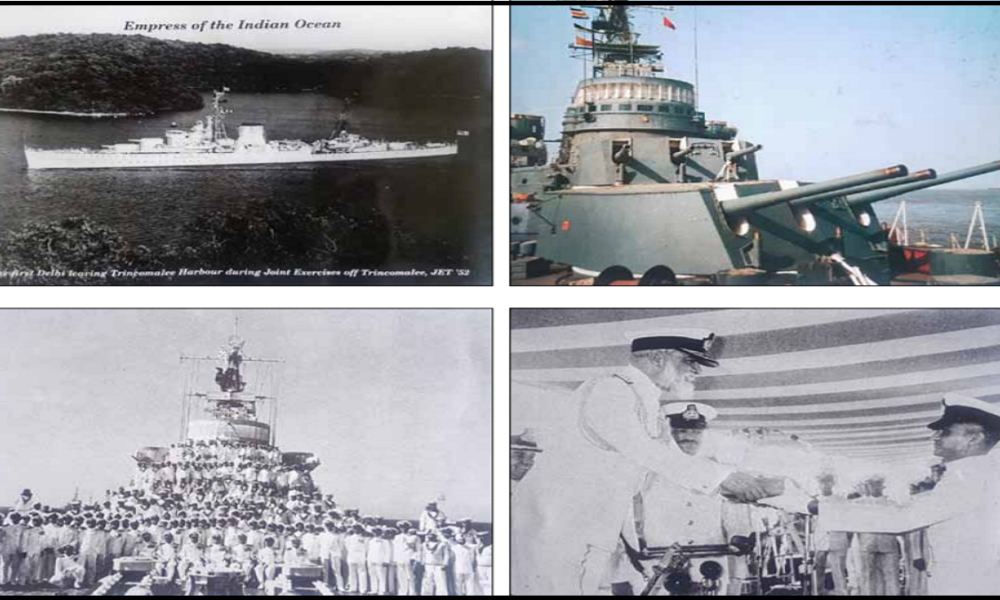

Seventy-two years ago, 5 July 1948, was a red letter day for India and Indian Navy. The newly independent nation commissioned the HMIS Delhi taking its first significant step towards a blue water future. While a ship by the same name, the sleek destroyer INS Delhi today prowls the seas defending India’s maritime interests, this piece is about its earlier incarnation which was Independent India’s first capital ship and, arguably, the most powerful in Asia in those years. A Cruiser with a glorious history (do Google HMS Achilles and the Battle of River Plate), acquired from the United Kingdom, she brought in the era of big ships in the Indian Navy which until then (and as the RIN) was operating much smaller ships. The then Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, was himself at the jetty in Mumbai to receive the ship when she came to India, two months later, in September 1948.

The seeds of today’s blue water Navy were sown, bit by tiny bit, since 1947. It must be noted that the British while developing a reasonably large Army and modest-sized Air Force for India, albeit for their imperial purposes, envisaged the Royal Indian Navy (RIN), the immediate predecessor of the Indian Navy, only as a coastal defence force. They were clear that blue water operations, sustained warfighting and ‘defence of the realm’ would be carried out by the Royal Navy. As Prof G.V.C. Naidu in his book Indian Navy and South East Asia (Knowledge World, 2000) says: “The colonial British Forces did not find it beneficial to expand the Indian Naval Forces, because the Royal Navy, then the largest navy in the world, was built especially to guard Britain’s overseas possessions and therefore, there was little need to build an Indian Navy” Even though the RIN expanded a great deal during World War II, it remained, essentially, a coastal defence and convoy protection force.

Thus, even as Independence loomed, the British naval planners did not want to consider a strong navy for their erstwhile colony. They desired to continue being in control of the sea areas in Indian Ocean and the Indian Navy was envisaged in a supporting role within the Commonwealth. In his book The Man who Bombed Karachi (HarperCollins, 2004) Admiral S.M. Nanda, referring to this period, says: “The manpower levels especially of the Indian Officer Corps were intentionally kept low and human resource development for manning and operating large ships were nil. If the Indian Navy had to be built it would have to rest on strong foundations. The only course was to create a strong core of professional officers and men who could build up the Indian Navy.”

Demobilisation after the war resulted in great reduction of the force and Partition truncated it even further resulting in independent India inheriting barely four sloops, two frigates and other smaller vessels. The biggest ones were in the range of about 1,000 tonnes. While such a state of penury may have suggested a conservative approach to naval development post-Independence, the Indian Navy was fortunate to have visionaries who dreamt big and far. Thus, our very first perspective plan unveiled in 1947 (Naval Plans paper 1/47), recommended the development of “a balanced Navy consisting of two Fleets, each to be built around a light aircraft carrier, cruisers, destroyers, auxiliary craft, submarine force and Air Arm”. This was dizzying ambition that most people may have scoffed at but our naval planners persevered and stayed the course despite many odds.

Delhi was the first acquisition that signalled our intent. While the plan was for three Cruisers, limited budgetary support meant that the second ship the INS Mysore (former HMS Nigeria, also with a glorious WW-II history) could be inducted only in August 1957. The arrival of Mysore in India, few months later in December 1957, was similarly celebrated with a tumultuous welcome and a reception hosted by the Prime Minister. While the Indian Navy acquired other ships such as the R class and Hunt class destroyers, it was the Delhi and Mysore that were the “jewels in the crown”.

The erstwhile Delhi and Mysore were our first big ships, our first Flagships. They had majestic looks and radiated menace with their bristling 6-inch guns and other firepower. They sailed around the world showing our Flag and earning us encomiums. They took part in wars and other operational missions. They trained the entire new leadership of Indian Navy and many who served on them went on to become Flag officers or served in high posts. They had a distinguished career in the Navy ending as training ships. In fact, the stories and legends associated with both ships are so many that they can fill a book. Almost the whole Navy shed a tear when they were decommissioned — Delhi in July 1978 and Mysore in August 1985. Above all, they had a huge role in the evolving Indian Navy and in our blue water journey.

Paradigm shift

Delhi and Mysore brought in a paradigm shift in the way the Indian Navy operated, in at least three very important ways. First, to be in the far seas, we need ships that are capable of doing so and we didn’t have that before Delhi and Mysore. The Black Swan and modified Black Swan class sloops, which we inherited, did not have the sea legs to venture far whereas Delhi brought in that capability with its big engines and boilers that yielded propulsion power of 72000 bhp on four shafts and a top speed of 32 knots, fuel capacity of 1,800 tonnes and accommodation spaces for nearly 700 people. To further illustrate, Delhi had a full load displacement of nearly 10000 tonnes, almost ten-times that of the Black Swans. Mysore was a shade bigger and more modern than Delhi, in all these respects.

The second aspect was in combat power. The 6-inch main guns of Mysore and Delhi were a huge capability leap in terms of the power projection. Each ship had three turrets including one in aft which dramatically increased their radius/arc of fire. In addition, these ships carried eight four inch guns, fifteen 40 mm guns, four three pounders for AA defence and eight 21 inch Torpedo tubes. In an era when power flowed from the barrel of a gun, this was a staggering leap from what earlier ships possessed.

Third, with this kind of combat power and sea legs you could not only venture to far seas but also show our flag in distant ports abroad and consolidate relationships. Much before our indigenous space or nuclear programmes came of age, it was the Navy that was showcasing our might in distant parts of the world. While the ships were no doubt British built, the fact that we had mastered operating and maintaining them were noteworthy as the world was just emerging from the shadow of colonialism. These ships engendered a kind of Asian and Third World pride. It is no wonder that Delhi was often described as “Empress of the Indian Ocean” and Mysore was called the “Queen of the Orient’.

Thus, they heralded the era of the big ships and laid the foundation for a growing navy. So whether it was in terms of Standing Operating Procedures (SOPs) or Standing Orders, the memoirs of Admiral R.D. Katari and A.K. Chatterjee (both of whom served as the Executive Officers of Delhi) bring out the challenges of transitioning to a big ship navy. Admiral Nanda who was the commissioning First Lieutenant of Delhi and Commissioning Commanding Officer of Mysore said, “Till then, all of us had been apprehensive of the word big. Everything seemed to be ‘big’ those days — even the anchor cables were ‘big’ and catting the anchor was a ‘big’ evolution.”

These two ships brought that change in mentality and we must remember that it happened at the dawn of Independence and the initial years thereafter. Hence, they proclaimed India’s intent to be blue water power quite early on. In the words of Vice Adm Narpati Datta who commanded Mysore, “Our generation of Indian naval officers had served mainly in small ships like sloops, minesweepers and corvettes in WW-II. Therefore, our first big ship, the cruiser INS Delhi was an instant favourite. As the Fleet grew in size and so did our experience in modern naval warfare, Mysore was there, a sleek cruiser with state of the art communication and command facilities.”

Operational highlights

Delhi as HMNZS Achilles and Mysore as HMS Nigeria were baptised in the fire of battle at sea during World War II. They performed equally well for a nascent Indian Navy in our many operations and missions. Both the ships saw action in Op Vijay for liberation of Goa, Daman and Diu in 1961. Mysore was given the task of capturing the Anjadip Island and liberation of Goa while Delhi was tasked to support the Army in Diu. Both played a significant role in quick and successful completion of operations, within 40 hours of commencement. It was the first recorded instance post-Independence wherein the ships of the Indian Navy had fired on an enemy in anger.

In the 1965 war, the Navy was given a restricted mandate of coastal defence, protection of SLOCs and directed not to operate north of the latitude of Porbandar, so as to not widen the scope of war. Mysore was the flagship of the Indian Fleet (Rear Admiral BA Samson) and successfully accomplished the mission despite the limitations. In 1971, Mysore was the flagship of the Western Fleet (Rear Admiral EC Kuruvilla), which achieved full sea control in north Arabian Sea that enabled our missile boat attack on Karachi, SLOC protection, capture of contraband, destruction of Pakistan navy and hastened the final denouement. In 1976, Delhi was involved in the salvage of the Godavari off Male, which was considered an extremely challenging task. As brought out by Dr Prabhakaran Paleri, the former Director General Coast Guard (DGCG), who served on both the ships, “They have fought real battles. The Navy is meant for reach and warfighting. These two ships have done just that in their lives. And that is why I will say that the INS Delhi and Mysore are models for the Indian Navy”.

It also bears mention they brought in new concepts into our operational lexicon. Command, Control, Communication (C3), Action Information Organisation (AIO), centralised external communications, modern fire control systems, concept of citadel and Nuclear Biological Chemical Damage Control and Firefighting (NBCD), all the terms in vogue now, came into being in some ways through the Delhi and (more through) the Mysore. As Vice Adm Datta brings out, “Nowadays we take these facilities for granted. But in the late 1950s it was a Fleet Commander’s delight to have his own and opposing forces disposition presented to him at a glance and to be able to talk to his ships and aircraft from the Ops Room.”

Above all, the real value of these two ships was brought out by Vice Admiral Subimal Mookerjee, former FOCinC, Western Naval Command, who said: “Delhi, Mysore and Vikrant were the principal elements of balanced deterrent Navy East of the Suez. This was a sine qua non for not only safeguarding our core national interests but also peace and stability in the region.” By the mid-sixties, a medium-sized task force comprising these three ships and other destroyers and frigates came to take shape. Within twenty years of Independence, our Navy came to be transformed from a coastal configuration to a force to be reckoned with.

Technical Development

It is axiomatic that such big ships and, modern ones by their contemporary standards, would have fairly complex machinery and equipment needing maintenance and repair. Delhi and Mysore, thus, engendered the development process that resulted in many changes and improvements in the Naval Dockyard at Mumbai. To maintain such a task force, the dockyard and the repair needed to be upgraded accordingly. The Bombay Dockyard, which had been in existence since 1735, hastened to modernise owing to these ships. The entire plan of the modernisation was divided into two phases with the Naval Dockyard Expansion Scheme (NDES) as the first phase, for twenty year duration from 1948 to 1968. Under this phase, many facilities such as the Ballard pier extension, the barrack wharf, the destroyer wharf and the Cruiser Graving (CG) dock came up in the Dockyard. The Duncan dock was upgraded for the first dry docking of INS Delhi and the CG dock was ultimately modified to dock the aircraft carrier Vikrant, which took place for the first time on 22 March 63. The second phase of the modernisation, again a 20 year plan, witnessed various facilities and infrastructure upgradation such as the steam test house, the REC department and the diesel and GT department. One of the major things that have come up during this phase was the construction of the South Break Water. All these initiatives saved the country millions of dollars which we might have spent to dock and repair our ships abroad.

Thus, the commissioning of these two ships not only triggered the modernisation plan in the Indian Navy but also influenced our top technical leadership towards a ‘Blue Water’ mindset. This is seen in the huge number of miles steamed by both Delhi and Mysore. For example, in the late sixties, twenty years after commissioning, Delhi steamed almost 30,000 miles, and many thought it wouldn’t have been possible. Similarly, Mysore traversed 20,000 miles on an overseas deployment in 1964. Adm J.G. Nadkarni, who served on board the Delhi both as the navigating officer and the Commanding Officer, totalled an astounding 100,000 plus miles cumulatively in his two tenures. In the words of Cmde S.K. Bhalla, the Commissioning NBCD Officer and (later) the Engineering officer of Mysore, “The Flagship has the onerous responsibility of leading the Fleet with speed and reliability.”

Competition between the two ships and others, whether at sea or in harbour, was intense but friendly. Delhi and Mysore would frequently race each other at sea. These ships often ran on josh plus prayer and when the Captains drove them hard, the engineers employed equal doses of innovation, improvisation, jugaad and will power to keep the hulks going. In his autobiography Memoirs and Memories, the legendary Daya Shankar, who served as the Fleet Engineer Officer on Delhi and went to onto become the Chief of Materiel and later Controller General Defence Production and is considered as the father figure of the Navy’s technical branch, recollects: “When high power was required and Delhi was running at top speed during manoeuvres the Boiler rooms were terribly unnerving places with all kinds of noise:the incessant roaring of forced draught fans raising the atmospheric pressure above normal, the continual bellowing of the huge sprayers and the scream of turbo feed pumps. Speech was impossible and terrific air pressure caused earaches. The continuing tension and unending noise racked men’s nerves. Since nobody could hear a word, engine room officers relied on gestures such as the flick of a finger or the rap of spanner on metal to get response from the artificers and stokers on watch. They instinctively understood the importance of being attentive to the situation around them and watching out for unforeseen danger signs”.

Training and Leadership

It has been brought out earlier that these ships were converted to training ships in the autumn of their lives. However, even before they donned that role they were excellent training ground for many in the Navy because of their unique mix of capabilities and adequate living spaces for personnel. Almost everyone went through their portals. The venerable late Vice Admiral M.P. Awati once said, “If Delhi is the cradle of naval leadership, Mysore was the kindergarten.” So, together, these two ships were the nursery of the modern Indian Navy.

Every activity on the ship whether it steaming the high seas, gunnery shoots, replenishment at sea, damage control exercises, hosting high dignitaries in India and abroad, seamanship evolutions including mooring to the buoy, watch-keeping in the bridge or the engine rooms, manning the weapons and systems, were enormous training value for everyone from Captain downwards to the junior most sailor simply because it was either new territory or being done on unprecedented scale.

Thus, it should be no surprise that almost all the Admirals of yore, our Chiefs, icons, war heroes – take your pick – almost all of them had spent some time onboard the Delhi or the Mysore and had earned their sea legs there. Almost the entire who’s who of the early Indian Navy — Katari, Karamarkar, Chakravarti, Soman, Chatterjee, Samson, Daya Shankar, Nanda, K.R. Nair, K.L. Kulkarni, Kohli, Cursetji, Krishnan,Vasu Kamath, Kuruvilla, S.H. Sarma, P.S. Mahindroo, Kirpal Singh, Narpati Data, Ronnie Pereira, Barboza, Swaraj Parkash, Ghandhi, Schunker, Awati, S.L. Sethi, Nadkarni, Tahiliani, K.K. Nayyar, I.J.S. Khurana, Subir Paul, Ramdas, Shekawat, Bhagwat, Madhvendra Singh, P.A. Debrass, J.T.G. Pereira, Bilu Chowdhury, Bhushan and so many others who are not mentioned only due to constraints of space — passed through the corridors of these ships and learnt the ropes of warfighting and leadership here. In fact, most of current top naval leadership have commenced their naval journey as midshipmen on Mysore learning the ropes of their trade on it, holystoning the deck, playing pranks in the gun room and bunking through the huge portholes.

Diplomatic dividends

The significant contribution of Indian Navy in our diplomatic endeavours is, by now, considered a truism. In 2004, a very visionary Navy Chief, Admiral Arun Prakash, instituted formal mechanisms for foreign cooperation by creating a dedicated Directorate for the same and establishing adequate staff structure under a two star officer. However, foreign cooperation and diplomatic interactions began for the Navy at the onset of independence and was given maximum impetus by Delhi and Mysore. These ships traversed all over the globe visiting nations in Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia engendering goodwill for the nation and building bridges of friendship. A panoply of monarchs, heads of nations and governments, defence ministers and military Chiefs, local elites and common citizens and the Indian diaspora visited these ships or hosted them in their port cities and each one left behind his or her own imprimatur and took away precious memories.

In fact, each of these visits, called Cruise in those days and Overseas Deployments (OSD) now, are worth separate monographs for their historical significance and rich kaleidoscope of experiences. For example, Delhi’s first cruise in 1949 and then in 1951 to East Africa, Prime Minister Nehru’s visit to Jakarta in 1950 on Delhi, Delhi’s cruise to Australia and New Zealand in 1969, Mysore’s cruise to East Asian ports in 1958 when she became the first Indian ship to visit China and Vietnam, Mysore’s four month visit to West Asia, Mediterranean, West Africa and East Europe nations in 1964 which included the first ever visit of our Navy ship to erstwhile Soviet Union, are recollected even today for the many milestones they achieved.

However, there were also political and social significance in these visits. While the big guns, and the brass and pomp impressed one and all, these ships also helped to create pride in Afro-Asian identity. Nations that had recently become free from their colonial masters or were still in the process of doing so looked up to India as the role model. Doubts were raised about the political unity of these entities, questions were asked about whether they could assimilate technology and this naturally created apprehension amongst the peoples in these nations. Vice Adm Katari, the first Indian Chief of Naval Staff who was also the commissioning Executive Officer recollects a talk by Admiral Arthur Power, the CinC Mediterranean, during the visit of INS Delhi, on her homeward leg, to Malta, “where he fulminated about developing countries having ideas above their station”. As the Indian Navy showcased our democratic ethos, our cosmopolitanism and our ability to master technology, it provided hope to many underdeveloped and developing nations. As Rear Admiral S.G. Karmarkar, who was Captain of Delhi said, “We proved to the world that we are a force to reckon with. We achieved what in the Royal Navy was labelled the ‘Mediterranean smartness and efficiency’. Our visits to foreign and friendly countries were always looked forward to with great pleasure and anticipation. The ‘Delhi’ stood out majestically with great dignity and slick appearance.”

Admiral S.M. Nanda, who was the commissioning First Lieutenant of Delhi and Commissioning Commanding Officer of Mysore, recollects a visit by Delhi to Mauritius in 1949: “For the Indian community in Mauritius the arrival of Delhi marked an emotional experience. Their forefathers had come as indentured labour. Now a warship from their forefathers’ country was paying them a visit. I recall three old men of Indian origin sitting on a quarterdeck under the Indian naval ensign. They did not leave till much after sunset when all the other visitors had left.”Or take the case of a visit to Mombasa in 1951 by Delhi when she hosted Jomo Kenyatta, the leader of Kenyan liberation struggle (and later the President of Kenya) when East Africa was still a British colony. Karmarkar reminisces, “I will always remember the look on Jomo Kenyatta’s face when he boarded the Flag ship. He said ‘Captain, the last time I boarded a British Cruiser it was as part of the chipping party. Thank you for all your kindness.”

Nanda also recollects the visit to Egypt by Mysore saying: “The Egyptians shared our pride in the power of our growing navy.” Manohar Awati recollecting the visit to East Asia in 1958 says, “People came in thousands… to see Mysore, the largest warship then serving in any Asian Navy. In fact, everywhere Mysore went she was besieged by curious and admiring throngs from littoral East Asia come to see the new Indian Navy. No mean distinction for India which until just ten years before was a thraldom.” He adds, “Mysore’s company was a virtual mini India. Well turned out, well behaved and excellently represented in sports and at social functions ashore, they were truly the Ambassadors of their country.” Incidentally, our performance in many of these sports competitions used to be outstanding further adding to the goodwill and respect for our navy and nation

X-Factor & interesting trivia

Beside all this, these ships also had a strange alchemy with their crew, the elements and with mother luck itself. It is what I would describe as the X-Factor. These ships were the closest to the Army in terms of regimental spirit and engendered huge amounts of loyalty and great spirit for the ship which came to fore in various ways. One of the most famous incidents relates to the fiercely fought boat pulling regatta at Cochin, in 1967, where the Delhi team came first but were disqualified having pulled in the wrong race. In one of those great annals of leadership, Ronnie Pereira, the Captain of Delhi, spoke to his team motivating them to pull again in the final race. Though limp with fatigue, the men raced against fresh crew of other ships and, incredibly, won the race again.

They produced some lovely literature. And lots of nautical trivia relates to these ships which could be of interest to history buffs and anecdote hunters. For example, it is said that the character of M from the James Bond movies is actually inspired by William Edward Parry who was the Commanding Officer of Achilles during the legendary battle of River Plate and then, by wonderful happenstance became the second CinC of the Royal Indian Navy. He was present at Chatham in July 1948 when Achilles became Delhi and, two months later, he was in India receiving the ship along with the Prime Minister. In a serendipitous occurrence, his Flag Lieutenant Swaraj Parkash went onto command the Delhi in late sixties followed by command of Vikrant during the 1971 war. Swaraj Parkash also happened to be the commissioning Navigating Officer of Mysore.

In the fifties Delhi very briefly went back to being Achilles while filming for a movie on the Battle of River, directed by the legendary David Lean, who embarked the ship for many days. Delhi also had the legend of the red headed ghost and the crew seriously believed that he always looked after the safety of the ship and, especially, the engineers and engines. Through the late fifties and sixties, the Mysore was a tourist attraction when anchored off the Gateway of India and it is said that tour operators on the boats operating to Elephanta Island charged extra for ‘commentary’ and ‘telescope view’ of Mysore. Both the ships were also reported to have excellent galleys and bakeries where the best fresh bread and cookies were baked and culinary excellence was the norm.

Adm A.K. Chatterjee had the rare distinction of being the Executive Officer of INS Delhi followed by taking over as the Commanding officer of the ship between Feb 1949 and October 1950. He had a second tenure as the Commanding Officer from 1953-54. Vice Adm N. Krishnan too had two tenures as Commanding Officer of Delhi, the second when he was briefly recalled for Op Vijay. Capt S.N. Kohli was present in the UK as our Naval Attaché in 1957 when Mysore was commissioned and Capt SN Nanda was the first CO. Subsequently, he took over Mysore from Nanda. He also took over the Command of Indian Fleet and a few years later, the Indian Navy from Nanda.

While most navy historians say that Indira Gandhi was the first woman to sail on Delhi, the distinction actually goes to Maniben Patel, the daughter of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, then Deputy Prime Minister who sailed on the ship in April 1950 with Maniben and his secretary V. Shanker. The distinction of being the first Indian woman to go across a jackstay is that of Meena Nagarkar, in Sep 1959, during a transfer from Mysore to Delhi. Meena was a lady plotter in Tactical School (now renamed MWC) at Kochi and the wife of the Officer in Charge ND School Cdr W.S. Nagarkar.

Mysore has the rare ‘status’ (if one can call it that) of having fired in anger on Indian soil as HMS Nigeria during an attack on Port Blair in June 1944 and on Nicobar in Aug 1945 and then as India’s flagship firing in anger against our antagonists. Incidentally, both Delhi and Mysore have the unique distinction of their commissioning and decommissioning falling on the same days. For Delhi, it was 5 July 1948 to 5 July 1978 and for Mysore it was 29 August 1957 to 29 August 1985.

The Second Generation

While many old-timers may have wanted their continued existence as national relics, it was not to be. However, the Indian Navy names new heirs after ships of yore to perpetuate the fine traditions and carry forward their legacy. Thus, Delhi, Mysore and, a new sibling, Mumbai, were reborn years later as destroyers. When the new INS Delhi was commissioned on 15 November 1997, the then skipper Captain (later VAdm) Anup Singh said, “Delhi has a unique role in the Navy, her name being synonymous with the Navy’s power and prestige. The predecessor of this ship carved herself with glory and we, the successors, are obliged to further enhance it.”

Future naval historians would probably see the commissioning of the three Project 15 destroyers in quick succession between 1997 and 2001 as equally landmark events. They ended a nearly decade long drought of accretion in our force levels. More importantly, these imposing, state-of-the-art ships bristling with high tech weaponry were designed by Indian navy’s design bureau and built in Mazagon Docks in Mumbai; thus, they were true ‘Make in India’ initiatives in which the Navy has been a pioneer.

While the first Delhi and Mysore was inducted at the dawn of Independence, the second generation were commissioned between the times when we celebrated the golden jubilee of our independence and becoming a Republic. The first generation signified the stirrings of hope and ambition of a nation and its navy; the second spoke of the long journey it has traversed and its achievements. This was a time-space continuum reflecting transition and transformation. The Delhi class and, their follow on ships, the Kolkata class continue to remain our most formidable assets and the Principal Surface Combatants around which the Fleet is built with the Aircraft Carrier as the fulcrum. .

Conclusion

They say ‘old soldiers do not die, they simply fade away’, but what about old ships? Mariners, since time immemorial, have believed that ships have souls, they have a sense of destiny, and they inhabit and roam around the seas long after their physical demise. While this may seem strange in the supposedly modern world that we live in, it is perfectly in sync with the ancient Indian belief of transmigration of soul and reincarnation. But ancient or modern, soul or no soul, not a single Navy man will dispute that ships, particularly warships, have a more tangible quality called the ‘spirit’ that is seen on a million different occasions. It, therefore, follows that ships with a great sense of spirit would be more remembered, more treasured and more admired than their counterparts.

Delhi and Mysore were such ships with spirit. Their respective mottoes ‘Sarvato Jayamichami (I Covet Victory Everywhere) of Delhi and ‘Na Bibethi Kadachan’ (Never Afraid or Forever Fearless) of Mysore provided inspiration to all those who lived and sailed on them. Their role in the nascent stages of our navy and nationhood needs recognition. Generations of Navy men had utmost reverence, love, nostalgia and affection for these grand dames. Today, the Indian Navy is in the big league of blue water navies. Let us take a moment to salute the spirit and memory of the two ships that were the the bedrock of our Navy and enshrine that moment on 05 Jul 1948 when the magnificent journey began.

Cmde Srikant Kesnur is a serving navy officer with interest in contemporary naval history