For three centuries, the al-Siraji Mosque, with its minaret fashioned from weathered bricks and its pinnacle inlaid with blue ceramic tiles, was a distinctive feature of the city of Basra in southern Iraq.

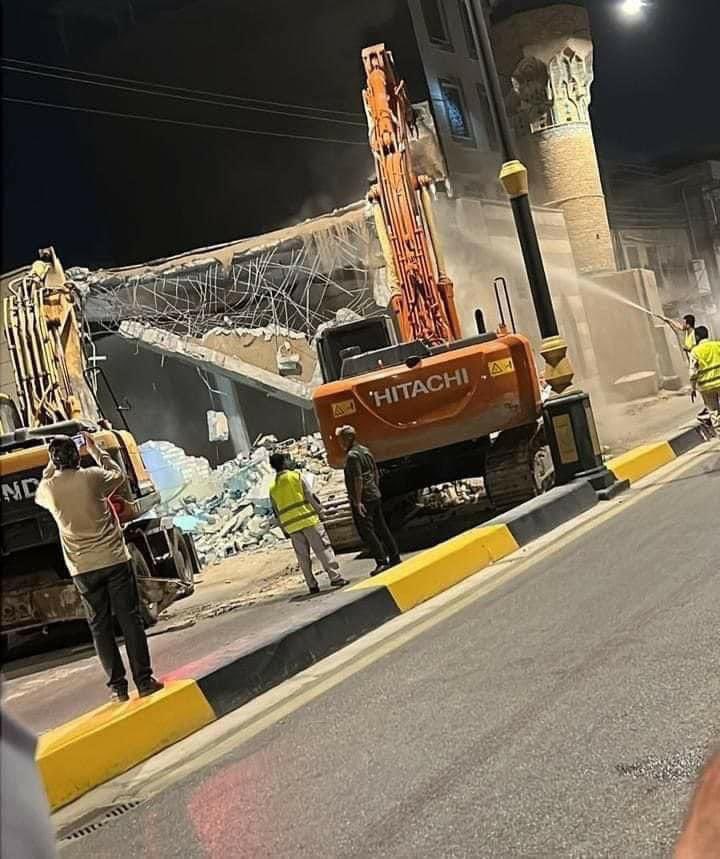

In recent years, it was one of the few tourist attractions in the oil-rich but neglected city, although locals complained that the minaret jutted out into the street, snarling traffic. In the early hours Friday morning, the 11-meter-high (33-foot-high) minaret was razed to the ground, with the governor of Basra attending the demolition, igniting a wave of social media backlash among advocates for the preservation of Iraq’s cultural heritage.

Heritage sites in Iraq, home to multiple civilizations going back more than six millennia, have been hard hit by looting and damage over the decades of conflict before and after the U.S. invasion of 2003. Most notoriously, the militant Islamic State group demolished numerous ancient sites in northern Iraq, including Islamic shrines, raising outrage among Iraqis and abroad.

Amid the relative calm that has prevailed in recent years, the country has seen a resurgence of archeology. Many stolen artifacts have been returned, and damaged heritage sites like the al-Nouri mosque in Mosul wrecked by IS have been restored after Iraq appealed for international funding to help.

“However, this time, it is the actions of official authorities that have put an end to our heritage,” said Jaafar Jotheri, an assistant professor of Geoarchaeology at Al-Qadisiyah University in Iraq.

The Siraji Mosque with its minaret was built in 1727. The mosque itself was not included in the demolition.

Basra’s governor, Asaad al-Eidani, said in public statements that the local government had received permission from Iraq’s Sunni Endowment Office, which has authority over Sunni religious sites, for the minaret’s demolition. He said the whole mosque would be replaced with a modern, better designed one.

“Some may say it’s historical, but it was in the middle of the street, and we took it down to expand the street for the public interest,” the governor said in a video posted on the official Facebook page of Basra Governorate Media Office.

The governor’s office did not respond to a request for comment. The minaret’s significance “lies not in its religious context, but rather its historical value,” said Adil Sadik, an architect from Basra. “This minaret does not belong to any individual or particular group; rather, it is the collective property of the city and a cherished part of its collective memory.”

The minaret’s destruction has drawn attention to the gaps in Iraq’s legal framework for heritage preservation. The country has two separate laws, the Antique and Heritage Protection Law and the Religious Endowments Law, which sometimes conflict. In the case of religious historical sites, the authority of the Endowments often supersedes that of the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage of Iraq. The incident has fueled a broader conversation about the preservation of Iraq’s historical sites and cultural heritage. After the uproar, the Basra governor said a Turkish company specialized in heritage preservation might take charge of rebuilding the minaret from the rubble. Jotheri said he doubts that’s possible. He noted that the bricks of the minaret were not numbered to allow for reassembly, and the use of a bulldozer damaged the unique features of the bricks.