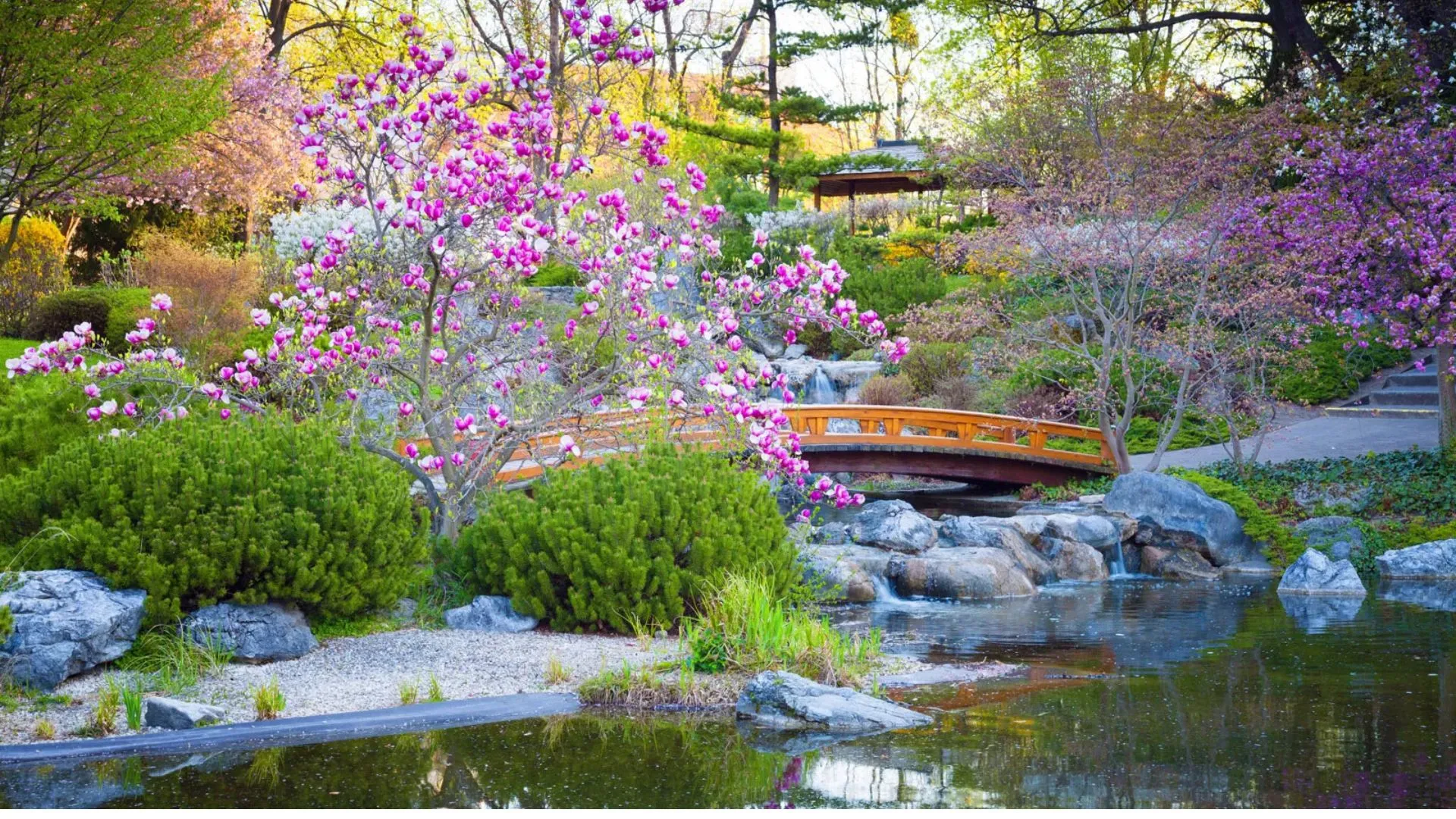

A small village nestles in the foothills of the Pir Panjal mountain range along the banks of the Wangath river. Surrounding it are picturesque meadows, lakes, and peaks that envelop you in an affectionate hug. This less-known village is Naranag, an ancient Hindu pilgrimage site in the Ganderbal district of Jammu and Kashmir.

At the feet of the mighty Buteshar (Bhuteshwar) mountains lies one of the most important archaeological sites in the country, the Naranag temple. In his historical account of Rajatarangini, Kalhana mentions that Ashoka built Srinagar city in the 3rd century BC.

It is interesting to note that the Wangath temples were built and expanded in three-time intervals, approximately at the same time as Shankaracharya Temple in Srinagar and Bumazuv Temple near Mattan. In around 220 BC, King Jaluka built the Shiva temples of Bhuteshwara, Jyestarudra, and Muthas around the spring site in Naranag. King Jayendra used the shrine to worship Shiva Bhutesha in 61 BC. After a victorious season, King Lalitaditya Muktipada (Naga Karakota Dynasty) made a sizable donation to the shrine between 713 and 735 AD. And lastly, between 855 and 883 AD, King Avantivarman assumed the job of building a stone pedestal with a silver conduit for the bathing of sacred idols at the shrine.

It is said that the temple was built as a dedication to the ancient Nagas. The Naga Karakotas were the Hindu Kashmiri Kayasthas of the Naga cult who were known for serpent worship.

According to his book, this shrine was looted by King Sangramraja of Kashmir (1003–28 AD) during the reign of King Uccala (1101–1111 AD). Later, it was also pillaged by a rebel Hayavadana. A notable western archaeologist, Sir Auriel Stein, revealed this information by translating Rajtarangani from Sanskrit to English.

In June, the Union Minister of State for External Affairs and Culture, Meenakshi Lekhi, visited the temple site to take stock of the state of affairs. A plan for restoration work on the complex is in place. Naranag represents the sacred architecture and cultural heritage of Kashmir.

The influence of architecture through these periods is what makes Naranag an archaeological wonder. Kalhana mentions how he used to accompany his father and uncle to the site and note these details. Local Muslims from the village have many tales from Kalhana’s book to feed the visitors’ curiosity.

One significant factor that sets this temple apart from others in the Valley is that temple complexes in Kashmir were either on the valley floor (like Mattan) or a hilltop (like Shankaracharya), but the Naranag complex surpasses the Sind Valley by the Naranag Nallah. The Greco-Roman architecture has its roots in the Gandhara Kingdom, which is evident in the Naranag temple as well; the fluted pillars and acanthus leaf decorations are some examples.

The many temples in the complex face each other at a distance of about 200 meters. Presently, only a few relics remain at the temple site—Siva Linghams scattered in the open, a large basin into which the spring flows, and temple pavilions. But the remnants tell a story of the grandeur of what this place used to be.

Such ancient temples built with large granite blocks were ordinary in Aryan Kashmir.

The vestiges were announced as a “protected monument of national importance under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and the Remains Act of 1958, years ago.