Regulations are important, but at the same time over-regulation creates ennui among the market players, discouraging them to invest their capital, technology and products/services. However, regulations cannot be overruled completely. Therefore, instead of having a discouraging regulation, emphasis shall be placed upon having encouraging regulations. The encouraging regulations aim to promote market growth along with ensuring prevention of adverse impact on the economy.

Introduction

On paper, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Guidelines for on-tap licensing of Universal Banks in the Private Sector (On-Tap Licensing Guidelines) provide for an elaborate, complex and multi layered prescription on ownership, to ensure control on ownership and quick dilution of concentrated holdings. But on a closer look, the On-Tap Licensing Guidelines are not only complex but are also discouraging for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the banking sector.

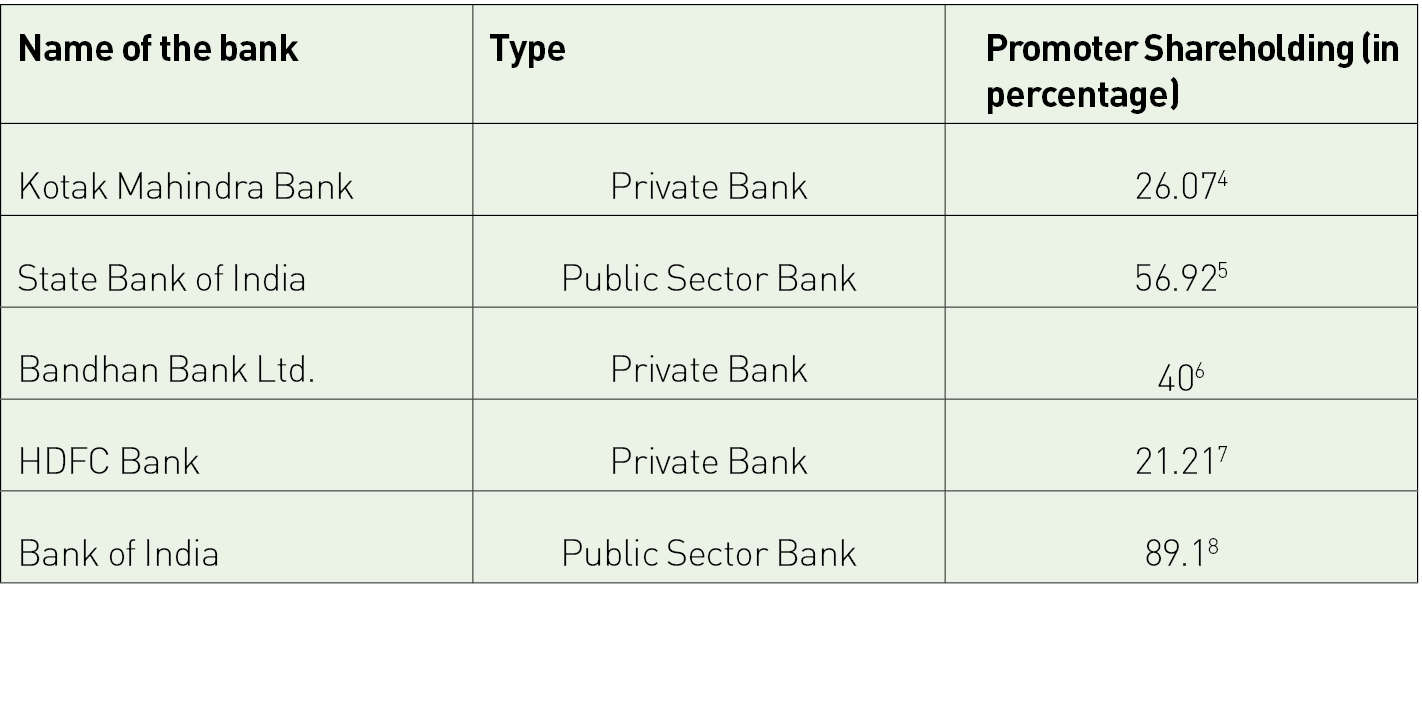

In the real world, private banks are experiencing differential licensing norms with relaxations being provided to certain banks by RBI. For instance, the promoter of Kotak Mahindra Bank is allowed to hold 26% shareholding, but when Indusland Bank’s promoter Hinduja brothers, wrote to RBI for seeking an extension in shareholding citing the Kotak Mahindra Bank relaxation, they had not received a nod pursuance to the same from RBI. Additionally, State Bank has been allowed to hold more than 48.21% in Yes Bank, while Prem Watsa owns a majority stake in Catholic Syrian Bank. This disparity creates confusion among the market players in relation to licensing norms and thus the same needs to be relaxed and revised as per market needs.

FDI limit vis-à-vis investment limit

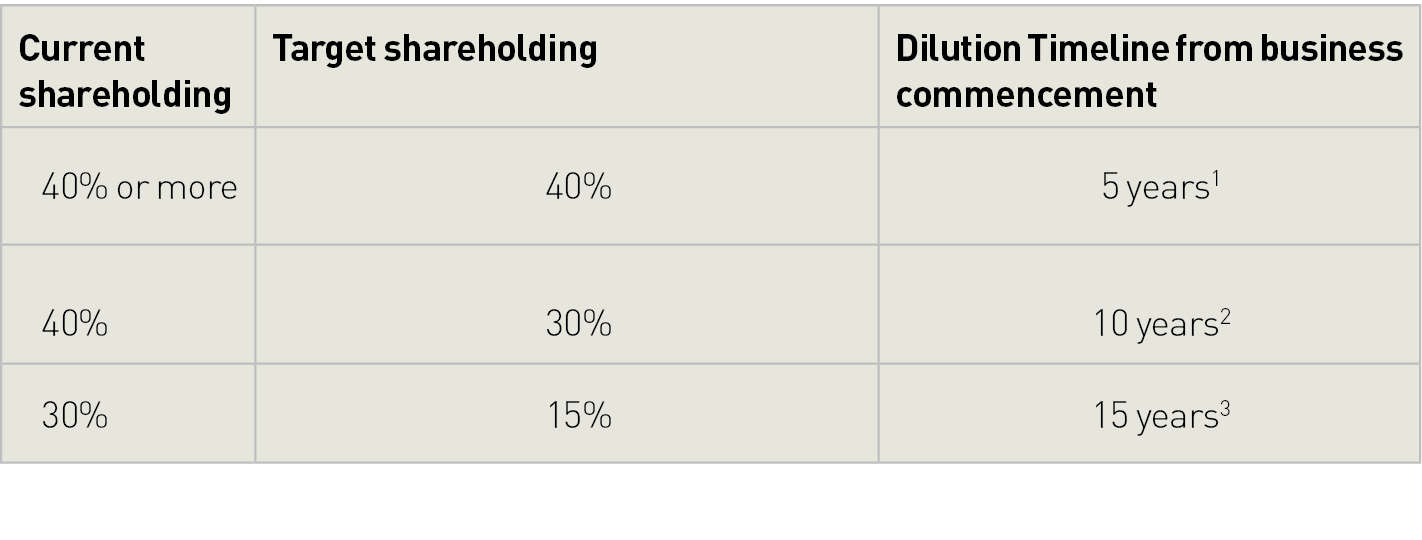

The On-Tap Licensing Guidelines provide that the promoter(s) and the promoter group shall have a minimum shareholding of 40 per cent of the paid-up equity capital of the bank on the date of commencement of business. The same shall be locked-in for a period of five years. However, any shareholding by promoter/s and the promoter group in the bank in excess of 40 per cent of the total paid-up voting equity capital shall be brought down to 40 per cent within five years from the date of commencement of business of the bank and the same shall be further diluted to 10 percent in 15 years in the following manner:

Additionally, no single entity or group of related entities, other than the promoters/ promoter group/ Non-Operative Financial Holding Company (NOFHC), shall have shareholding or control, directly or indirectly, in excess of 10 per cent of the paid-up voting equity capital of the bank during the first five years of the operations of the bank.

On the other hand, the permitted FDI limit for private banks is 74%, out of which 49 per cent FDI is allowed under automatic route and remaining through the government route. So, even if the foreign investor invests within the automatic route limit of 49 per cent, he can anyway not invest less than 40%. At the same time, if he takes the pain to avail approval and invest from 49% to 74%, he will be forced to dilute to 40% within a commercially unfeasible timeline of 5 years. By 15 years, every foreign investor is left with the limited shareholding of 15% and no skin left in the game to promote its Indian subsidiary (if at all it can be called one). The banking and finance sector has long gestation periods. When an investor decides to open a bank, he expects to be in a jurisdiction for the long haul. This makes the permitted FDI limits commercially not viable. This is evident also from the lack of presence of the top foreign banks in India and the even greater lack of innovation in the sector.

As per the International Monetary Fund (IMF), India is the fifth largest economy in the world in terms of gross domestic product (GDP). However, the Indian banks failed to feature among the top 200 banks in the world. This indicates the need to alter the regulatory structure to revamp the banking sector, with sufficient scope and space for the foreign investors to invest and operate in India.

Fair Market and Level-Playing Field

To really understand the preferential treatment to public sector banks in India as against the harsh norms for private banks, we can simply refer to their shareholding concentrations:

This treatment towards the promoters of public sector banks as opposed to the public sector banks creates a barrier to entry for the new private players. The public sector banks in India enjoy the privilege of perpetual continuity, merging into each other and heading towards one gigantic public sector bank. Further, the continuous reduction in promoter shareholding, shall lead to drop out by the existing market players. This is leading to dangerous levels of market concentration which is not feasible in the long run. There is a need to rectify this differential requirement in order to preserve competition.

Re-evaluating the impact of nationalisation

Although the credit growth decelerated in the case of both private banks and PSBs in the fiscal 2019-20, however, the statistics from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) show that credit growth is mainly driven by private banks. The data provided in the table below also reveals the resilience of private banks in the face of tectonic shifts.

So far, the allocative efficiency and resilience of public sector banks is concerned the same is driven by regulatory reforms such as the Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) Framework, in absence of which some of these PSBs would have incurred even higher losses and required even more money for recapitalization. Similarly, In a similar fashion, the private banking space shall also be channelized with adequate supervisory and regulatory norms. However, in order to maintain the operational freedom over-regulation shall be avoided.

Failing financial inclusion goal

The bank nationalization was driven by “social outlook” for better penetration of lending and banking activities across India. Despite the provision of bank accounts to almost every household in the country with the launch of Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojna (PMJDY), the World Bank data reveals that half of India’s bank accounts are inactive. The World Bank’s Global Findex Database 2017 states that less than 10% of Indians have access to formal credit. This implies that less than 76% of the Indian population cannot access formal credit.

Thus, the entire scheme of financial inclusion seems to have failed to surface into reality. For a country like India with vast population, there is a need for a system with such channels and intermediaries that allows access to financial services to the wide net of customers, both rural and urban. However, there are only limited channels for smooth access to basic financial services across the geography. Therefore, there is a need to increase foreign participation with innovative products/ services and advanced technical support to enhance customer outreach and in-depth penetration of financial services within the social structure.

What regulation is best regulation?

Regulations are important, but at the same time overregulation creates ennui among the market players discouraging them to invest their capital, technology and products/ services. However, as regulations cannot be overruled completely. Therefore, instead of having a discouraging regulation emphasis shall be placed upon having encouraging regulations. The encouraging regulations aim to promote market growth along with ensuring prevention of adverse impact on the economy. The provision under the OnTap Licensing Guidelines providing for continuous reduction in the shareholding pattern is in the nature of discouraging regulation which tends to discourage foreign investors. Therefore, such discouraging regulation shall be substituted with such regulations which cater to the requirement of market regulation as well as promote business. Thus, the reduction in shareholding shall be replaced with other regulatory requirement to alleviate the operational burden. For instance, the requirement of maintaining a specific statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) shall be incorporated to assure sufficient liquidity as security measure rather than the requirement of reduced promoter shareholding. Therefore, RBI shall consider incorporating similar encouraging regulations which are neither detrimental for the concerned stakeholders for them to effectively contribute in the economy. Alternatively, having stringent regulation shall affect the ease of doing business.

Conclusion

According to the World Bank forecasts, India’s economy is registering an upward trend in the longer run despite the odds created by Covid-19 pandemic. However, to sustain the pace India needs to continue with the liberalized norms in the financial sector.

Globally, digital forms of banking are emerging as an alternative to traditional banking model with models such as neo banks and modular banking/ Banking as a Service (BaaS). On the other hand, India does not have neo banks with existing banks struggling to tie up with fintechs to create a pandemic resilient technological platform. Innovation in the sector is lagging with lack of promotion of foreign investment and ensuring skin in the game for private players in the long run. There is a need to allow greater foreign investor participation or private participation with perhaps higher ongoing compliance requirements to bring in greater fair market competition, efficiency and innovation in the sector.

Alternatively, the newly established International Finance Services Centres Authority can provide the existing GIFT-City as a pilot for experimenting with relaxed foreign investment norms and experiments in innovation. But even for the IFSC project to succeed, India needs to change its global perception of being a highly traditional banking market with limited scope for manoeuvring and experimentation.

Mr Ajaya Kumar Sahoo, Former Officer, Reserve Bank of India and Mr Anuroop Omkar, Director, Bridge Policy Think Tank