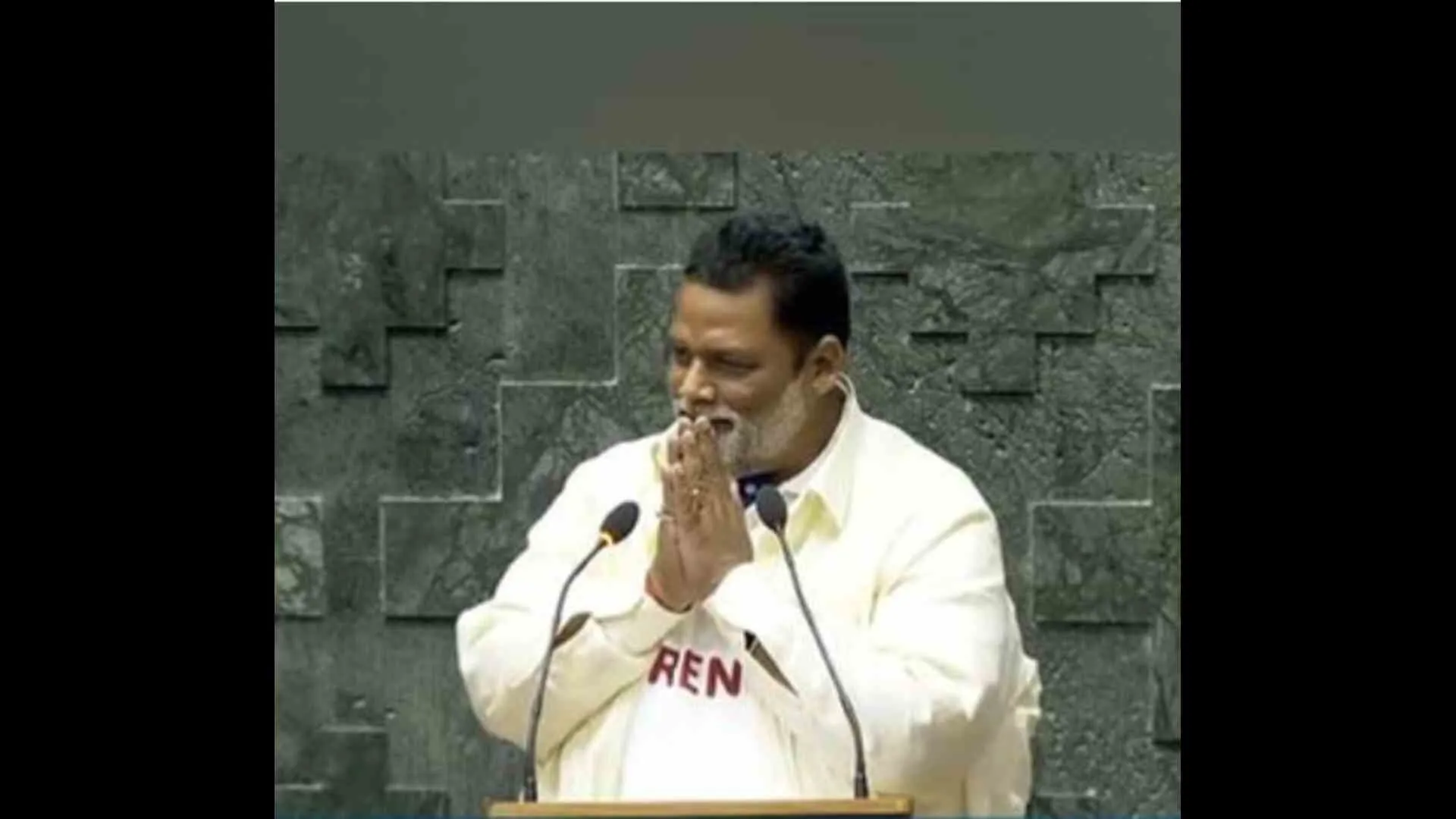

Following is the text of the Intervention made by Union Minister of Commerce & Industry, Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution and Textiles, Shri Piyush Goyal on Fisheries Subsidies Negotiations during the 12th Ministerial Conference of the WTO in Geneva:

“India is a strong advocate of sustainability, and its glorious history speaks volumes of its traditions, customs and good practices in managing its natural resources. At the same time, I urge you to take cognizance of the fact that many nations from both hemispheres allowed their gigantic industrial fleets to exploit and plunder the ocean’s wealth over the past several decades, leading to highly unsustainable fishing. In contrast, India maintained fleets of modest size that largely fished in its Exclusive Economic Zone, operating with passive gear and leaving bare minimum footprints on the seascape.

Our subsidies are one of the lowest; we are a member only in one RFMO, and we are not a distant water-fishing nation. We don’t operate huge fishing fleets to exploit the resources indiscriminately like any other advanced fishing nation. I have before me a chart which shows the vastly differing subsidies given by different nations. India, for every fisher family that we have, gives barely $15 in a year to its fishermen families and there are countries here, which give as high as $42,000, $65,000 & $75,000 to 1 fishermen family. That is the extent of disparity that is sought to be institutionalized, through the current fisheries text.

India’s fisheries sector is traditional and small-scale in nature and we are essentially one of the disciplined nations in sustainably harnessing the fisheries resources.

Excellencies, Fish is an inseparable part of Indian mythology, religion and culture. India’s engagement in the sustainable harnessing of its fish & aquatic resources has always been exemplary. The traditional fishers’ life in India has been intertwined with the oceans and seas since times immemorial. Fish is the only source of their livelihood over generations; responsible and sustainable fishing is ingrained in the ethos of our fishers. Our traditional fishers toil under harsh and extreme conditions to bring the highly delicious and nutritious fish protein to our plates & to the plates of many other countries.

In spite of abject poverty and illiteracy, Indian Fishers practice voluntary restraint for 61 days in a year to allow Fish to grow and regenerate. They may go hungry but do not venture into the seas during these 61 days. In fact, as we speak today, there is no fishing happening in my country anywhere. On the West coast, where the Arabian sea is, and from where I come from, it is stopped from 1stJune to 31st July. In the Bay of Bengal, in the East, it is stopped from 15th April to 14th June to allow the fish to breed & regenerate. Our traditional fishers are mired in deep poverty and their only asset is a boat and net.

I strongly feel that this outcome of the exercise being carried out now, has not provided a level-playing field to the developing nations to address the aspirations of the traditional fishers and their livelihood. Several million fishers, nearly 9 million families in India depend on assistance and support from the Government, albeit very small which I just demonstrated, for their livelihood. Any decision not to provide space for small-scale and traditional fishers to expand their capabilities would only rip away their future opportunities.

It may not be out of place to say that several advanced fishing nations are indiscriminately exploiting the fisheries resources in others’ EEZ and the high seas by being members of multiple RFMOs. India has argued in the past that such nations shall own the responsibility for the damage they have caused to the global fisheries wealth and should bring them under a tougher discipline regime. Still, to our distress, the present text does not stop such over-exploitation; instead, it indiscreetly allows such practices indefinitely.

Incidentally, I see a lot of countries very concerned about their fishermen. But what are the number of fishermen? One may have 1,500 fishermen, another may have 11,000 fishermen, another has 23,000 fishermen, and yet another 12,000. The concern of the small number of fishermen prevails over the livelihood of 9 million fishermen in India. This is completely unacceptable! And that is the reason, India is opposed to the current text, also opposed to the way De minimis is sought to be institutionalized. I see in every which way, the Uruguay round assymetries and discrimination in agriculture being sought to be institutionalized in fishing today. And I would urge all the developing countries to beware of such efforts. To be cautious while we mortgage away our future and the future potential of our poor people to grow, to become more prosperous in the future and to get a chance, a better chance in life.

In fact, India has been able to sustain its fisheries wealth, providing livelihood to its millions and food and nutrition to its growing population, because we have kept sustainability at the core, yet given them an opportunity to fish in our economic zone (EEZ). It may not be out of place to state that the developing nations have been a mute witness to these unsustainable exploitation of fishery resources by industrial fishing fleets of the distant water fishing nations. As the FAO status of the World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020 Report suggests, there are an estimated 67,800 fishing vessels of at least 24 meter length. It further reported that the proportion of these large vessels was highest in Oceania, Europe, and North America. A recent study, (Rousseau et al., 2019) found that the large fishing vessels, making up only 5% of the fleet constituted more than 33% of the total engine power.

A recent article research published in Science Advances on the Economics of fishing the high seas (Enric Sala et al 2018) alludes that high sea fishing at the current scale is enabled by large government subsidies, without which as much as 54% of the present high seas fishing would be unprofitable at current fishing rates. India would once again like to reiterate its position that advanced fishing nations own the responsibility of the damage caused to the global fisheries wealth especially in the high seas which are also the common heritage of the humankind.

In this context, we would like to emphasize that ‘common but differentiated responsibility’ and ‘polluter pays principle’ should be the bedrock of any agreement related to sustainability.

India would strongly urge that Distant Water Fishing Nations should be subject to a moratorium on giving any kind of subsidies for 25 years for fishing or fishing-related activities beyond their EEZ. It is essential, that they transfer these capacities to the Developing countries and LDCs to give them a chance to grow.

It would be a matter of great concern for India such Distant Water Fishing Nations are provided carve out under the shelter of conservation and management measures in the draft Ministerial Text on fisheries subsidies (article 5.1.1).

On the contrary, we see from the current text that the subsidies extended by the developing countries to their millions of small-scale and artisanal fishermen for meeting their genuine needs and enabling their access to fishing for livelihoods in their own EEZ is subjected to scrutiny with the onerous responsibility to demonstrate sustainability. We cannot not agree to such an imbalanced text.

Subsidies like income and livelihood support during the seasonal no fishing for regeneration of fish stock, and provision of social security nets to the socially disadvantaged fishing communities cannot contribute to overfishing. Such subsidies in fact contribute to the reduction of vulnerabilities of the poor fishing communities who work in extremely harsh environment.

We must also be mindful of the fact that the ecosystem attributes of tropical waters are different from the temperate waters and in tropical waters the regeneration of the fish stocks is much faster vis-à-vis the temperate waters and therefore the same yardstick cannot apply.

Similarly, a de-minimis on the global catch basis without reference to the fishing, the fishermen families involved, the size of the nation, the size of the population being supported is a completely arbitrary and unfair situation.

Whether point 7 or point 8, it does not take into account that an African country maybe supporting 220 million people population or possibly supporting a very large number of fishermen against another country which maybe supporting a 2 million – 3 million population and ten thousand fisherman, how can the de-minimis be the same for all sets of people.

We are also extremely concerned with the proposed prohibition limited to only specific fuel subsidies and leaving out the non-specific fuel subsidies. In the total fisheries subsidies, the share of fuel subsidies is estimated to be around 22 percent, which is mostly in the form of non-specific fuel subsidies. Through this agreement, we are trying to address the issue of sustainability. Leaving out disciplining non-specific fuel subsidies has no justification in the science of fisheries conservation. The Agreement would negate the objective of sustainability as envisaged under SDG 14.6 and our resolve to stop subsidies for IUU fishing.

The transition period of 25 years sought by India is not intended as a permanent carve-out, it is a must-have for us and for other similarly placed non-distant water fishing countries. We feel that without agreeing to the 25-year transition period, it will be impossible for us to finalize the negotiations, as policy space is essential for the long-term sustainable growth and prosperity of our low income fishermen.

The exemption from disciplines for the low income or resource-poor or livelihood fishing particularly again for those nations not involved in long distance fishing up to our EEZ i.e. 200 nautical miles, is highly essential to provide socio-economic security to these vulnerable communities. This will allow us to disperse the fishing operations of the low income, resource poor, small-scale and artisanal fishers deeper in the EEZ in order to reduce the fishing pressure in the nearer to coast regions. While urging for this exemption, it may not be out of place to state that Members have a sovereign right to explore, exploit and use the resources within their jurisdictional waters. We are also mindful of the responsibilities bestowed on us while exploiting the resources in our own sovereign waters.

We are strongly of the view that the outcome of this exercise should provide a level-playing field to the developing nations to ensure that their small-scale and artisanal fishing fleets are sustained, and the livelihoods of their resource-poor fisher people are not threatened, food security issues are adequately addressed, and there is policy space for all maritime zones including the high seas, which should be provided to meet the growth aspirations of the traditional fishermen communities. We would also like to emphasize on providing time and space to enhance the capacities of the developing nations in resource management, fleet optimization, wherever required and taking this onerous task of meeting the requirements of the final outcomes of the fisheries subsidies to the last mile. We have always played a very active role in this long and arduous journey, we are often told that this is some last minute thought we have brought out, I will strongly contest that we are on record since long on many of the issues that I have raised here today. I know I have been long but I thought it is necessary to open the eyes of this august assembly to the deep concerns of the low income countries and the developing world and the developed nations to the huge disparity sought to be foisted on us once again like it was done in Agriculture 35 years ago.

In conclusion, India would like to remind that the United Nations General Assembly has declared 2022 as the International Year of Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture, let us all join hands to ensure that the outcomes of the fisheries subsidies negotiations provide the right support, balance, equity and thrust to the artisanal and small-scale fishers, who are also the backbone of global fisheries. By doing so, we would not only be honouring the decision of the UNGA but also paying a glorious tribute to the millions of fisher folk all over the world.”

Subsidies like income and livelihood support during the seasonal no fishing for regeneration of fish stock, and provision of social security nets to the socially disadvantaged fishing communities cannot contribute to overfishing. Such subsidies in fact contribute to the reduction of vulnerabilities of the poor fishing communities who work in extremely harsh environment.