In Bombay, the IPTA had set up a special unit for dancers and musicians, the Central Cultural Squad, which was funded by the Communist Party. Shanti Bardhan joined as its chief choreographer and was assisted by fellow Almora alumni Sachin Shankar, Narendra Sharma, Prabhat Ganguly and Ravi’s brother Debendra. Ravi was offered the role of music director. Confused and upset about the situation with his wife Annapurna and Kamala (whom he fell in love with but was married off to Bengali director Amiya Chakravarty), he grasped this opportunity and moved into the squad’s headquarters at Khushru Lodge.

He made it clear that he was not a communist but like almost all Indian artists at the time he had leftist leanings. He shared the enthusiasm for native Indian arts over European forms and identified with the collaborative, egalitarian ethos and the anti-imperial message. He publicly lamented that India was ‘a country under foreign yoke and education, where musicians starve’, but his instincts were optimistic rather than angry. ‘With the people awakening to their cultural heritage, to the wealth of their musical riches, folk, secular, devotional and classical, a new era is dawning,’ he wrote. Music could herald a bright future.

Khushru Lodge was a mansion in the suburb of Andheri East. It had a spacious garden with coconut palms, mango trees and a huge hundred-year-old banyan. This was both workplace and residence and was run as a cross between a commune and a militia. Everyone woke at five, took breakfast together at 6.30 am and began working at seven.

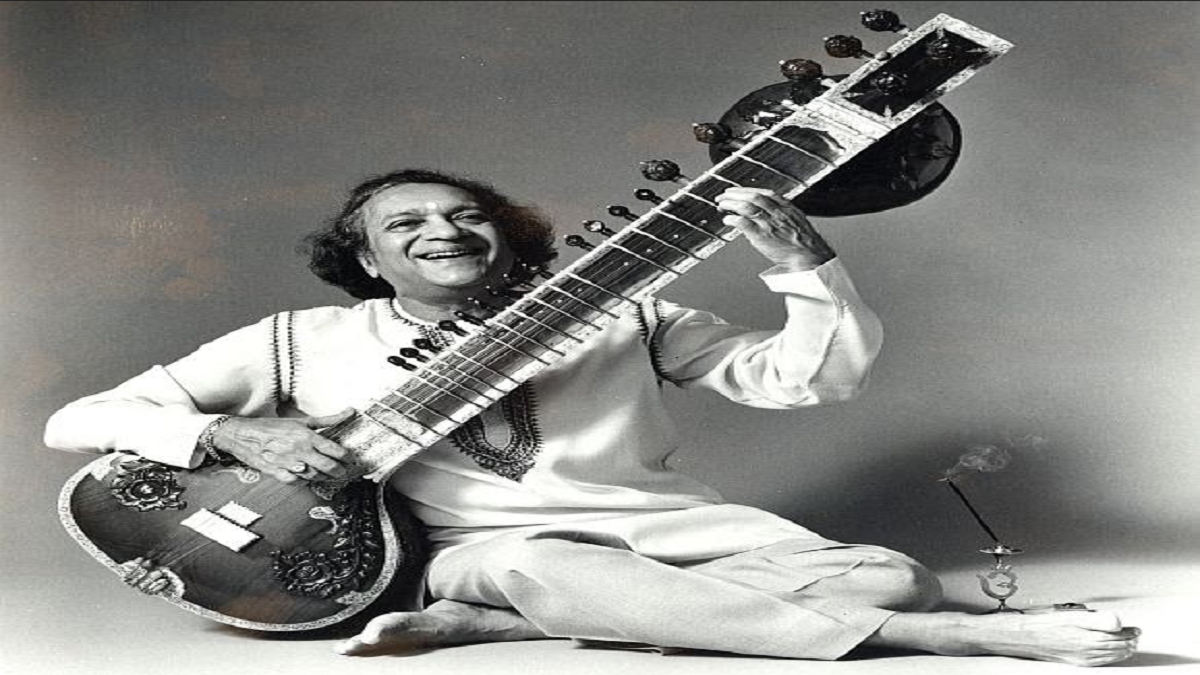

Ravi liked the disciplined environment and in turn, he made a very positive impression on the movement. There were, he recalled, more ‘green signals’ from women staying at the house, but he was in a celibate mood. At the end of the working day, he often practised sitar until late at night. ‘Even today I can visualise him doing that on moonlit nights on the roof of the veranda,’ said the writer Rekha Jain, who was studying dance there. ‘The notes from his sitar seemed to touch our very heart-strings.’

For the next few months, Ravi immersed himself in work and practice and thrived on it. He had artistic freedom, he had a corps of musicians and dancers to teach and train, and there were exciting projects. For the first time, he was composing for the stage. Before he joined, two IPTA dance productions, Bhookha Hai Bengal and Spirit of India, had toured with some success and another production was planned: India Immortal. This was billed as ‘a patriotic ballet’ and presented a history of India told through dance.

Ravi felt inspired and found that music flowed out of him very quickly. He loved working with his friend Shanti Bardhan, whose roots were in the dance of his native Tripura. He was similar to Uday in his approach to choreography, combining inventive modern dance with Indian classical and folk styles. In late 1945 and early 1946 India Immortal went on a tour of north India, taking in Calcutta, Patna, Delhi, Kanpur, Lucknow, Lahore and Bombay.

Soon afterwards, Ravi was asked to make his debut as a film composer. Two commissions came along at almost the same time through the IPTA. Both were films that championed the downtrodden in society; they pioneered social realism in Indian cinema and were influenced by the work of Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin in Russia. Dharti Ke Lal (‘Children of the Earth’), the directorial debut of K.A. Abbas, dramatised the horrors of the Bengal famine. It was developed from the Bengali IPTA play Nabanna which had toured widely in aid of famine relief.

The film gave the first major screen roles to Balraj Sahni, Shombhu Mitra, Tripti Bhaduri and Zohra Segal. This was the only film that the IPTA actually produced but the collective did give support to the other film that Ravi worked on, Chetan Anand’s debut, Neecha Nagar (‘The City Below’). Based on Maxim Gorky’s Lower Depths, this is the story of a rich landowner who knowingly diverts the sewage from his hilltop mansion to pollute a village in the valley below. The villagers fall sick and it is the death of Rupa, played by another screen legend in her debut role, Kamini Kaushal, that inspires the villagers to militant protest. It also starred three other members of the director’s household, Uma Anand, Hameed Butt and (once again) Zohra Segal.

Ravi’s music was crucial for the emotional impact of both films. He saw his choral effects in the title sequence of Dharti Ke Lal as ‘endeavouring to capture the wail of humanity uprooted from its home and on the march in search of food and shelter’.

For Neecha Nagar he wrote rousing songs — based on classical ragas — for the villagers who rise up in protest. But it was in the incidental music where his contribution was most significant. In the fifteen years since India had first made films with sound, most of the industry’s musical focus had been on the songs, with less thought given to what happened in between them.

‘I have always felt that the purpose of background music is not merely to fill the silent gaps in a film,’ Ravi wrote in 1958, ‘but to enhance the mood of the picture and endow it with a poignancy which words and actions cannot convey.’ He believed that songs and incidental music should play equally important roles.

At a time when Western orchestral arrangements were the norm for Indian films, he also went against received wisdom in believing that Indian classical music could render the full range of required emotion and could do so using small ensembles of Indian instruments. Ravi was particularly happy with the music in Neecha Nagar, and found it rewarding to work with Chetan Anand, who was a good violinist and had a sensitive ear.

Both films were made against the odds, the inexperienced casts and crews having to contend with low budgets and rationing. They had to apply for special wartime licences, only three of which were granted to independent filmmakers (the third went to Uday’s dance epic Kalpana). Ultimately the films were too demanding for a general audience and both flopped at the domestic box office, although they were critically acclaimed and proved to be influential.

At Cannes in 1946, Neecha Nagar won the Grand Prix, the top prize at the time, although uniquely in that first year of the film festival it shared the honour with ten other films, among them Brief Encounter and Rome, Open City. As for Dharti Ke Lal, after receiving Stalin’s personal approval, in 1949 it became the first Indian film to be dubbed into Russian, opening up a huge market for Indian cinema in the Soviet Union.

However, Ravi’s soundtracks sank without trace. Then as now, film songs were India’s popular music and a film could succeed or fail depending on the appeal of its songs. A few years later and Ravi’s songs might have achieved some broadcast coverage but radio was still in its infancy in India.

‘The films had such scattered and short runs that the songs had no chance of becoming popular. Promotion by radio did not exist then,’ Ravi said. That said, his songs would by their nature have probably struggled to make an impact outside the cinema.

The film music fashion of the moment was the dholak beat, introduced by the 1944 hit Rattan, which sold gramophone records in the thousands and established Naushad as one of Bombay’s leading music directors. Ravi came to accept that he had been ‘innovative ahead of the times… My compositions were wedded to the theme so closely, welded in fact, that they hadn’t a chance with the public unsupported by the film.’

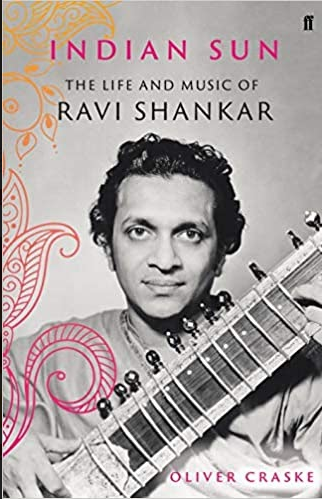

Excerpts from Oliver Craske’s book, ‘Indian Sun: The Life and Music of Ravi Shankar’, published by Faber & Faber, Rs 899.