In this moment of environmental crisis, there’s little point in listing out the major ecological issues facing the subcontinent — borne out of culture, geography and even geopolitics. And unsurprisingly, artists and creatives across South Asia are addressing this state of emergency head on.

The 2020 Lahore Biennale addressed climate at its core, asking “how might we reflect on our place within the cosmos today, at this conjunction of planetary climate crisis and polarities between societies?”

There has been a marked recent shift into activist climate-centric art, led by an array of interdisciplinary thinkers from across the subcontinent. The output has been as surprising as it is exciting.

What has emerged is a group of creators across South Asia who bridge the sciences and the arts: Artists, filmmakers, professors, architects, and writers — each of whom is telling the story of our times.

Their work addresses suffocating urbanisation and infinitely destructive construction and development projects, population growth, the absence of sanitation and sewage infrastructures, animal farming, the destruction of tenuous natural ecosystems and a lack of regulation and layers of incompetence, corruption and negligence in conservation and preservation.

Multi-faceted in vision, approach and experiences, they include trained doctors, lawyers, even computer scientists who are making films, presenting installations at biennales, writing poetry — responding to our shared environmental crises through their varied practices.

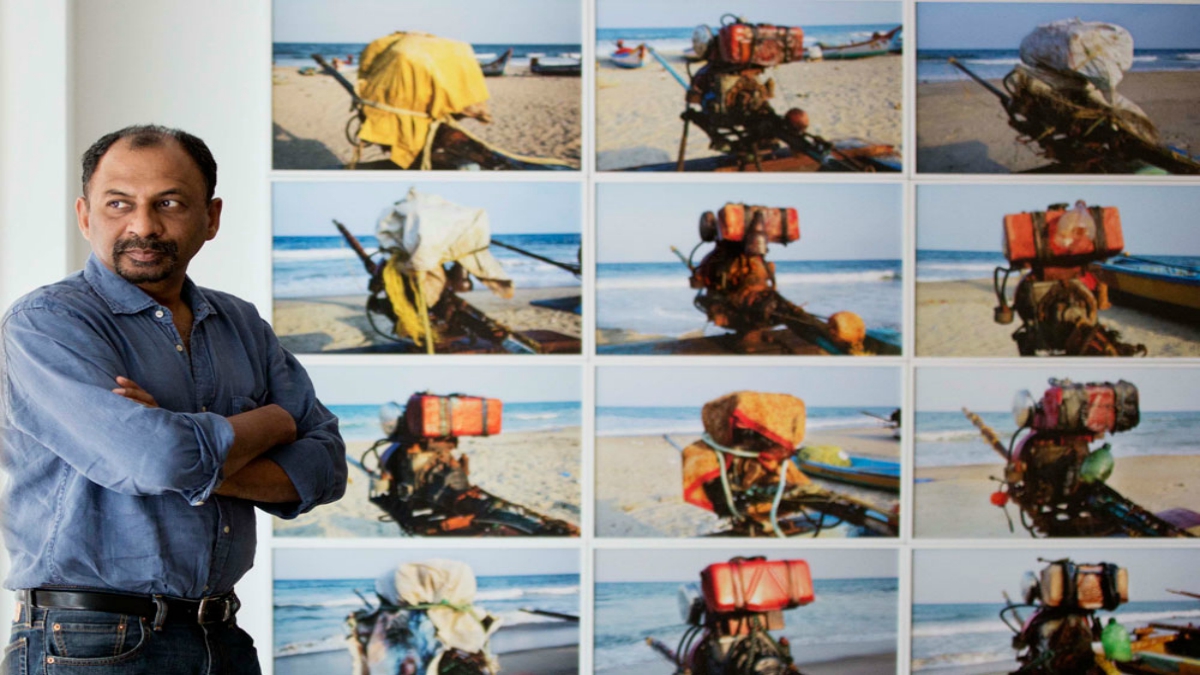

Artists like Ravi Agarwal who have for decades worked across creativity and science are having a unique moment — climate change and the environment seem to present a lyrical confluence of these two halves of our world: Our planet, our humanity, and the science needed to protect it.

One of India’s most well known contemporary artists and photographers, Agarwal’s work has been exhibited at Sharjah, Kochi, India Art Fair; and yet in his “day job” he is the founder director of the environmental NGO Toxics Link and has pioneered work in waste and chemicals in India.

And increasingly, creative practitioners are defining themselves as activists for the planet and reaching outside of the bounds of the art world in their collaborations.

Artist and professor Risham Syed digs deep into the urbanisation of Lahore and aligns with a civil society-led resistance to the fast and mad construction over fertile land, the destruction of the Ravi river, overcome by greedy developers and the requisite grasping administrators and stakeholders.

Syed’s students are part of the journey for change with her, the community she brings to the fore in her work. There is strength in diversity, and there is a power from younger voices as much as from the established stars in this field.

Artist studies on water

What feels most central and inexorable for the art world of the Indian subcontinent today remains the issue of water. Running through as a connector — like the seven major rivers of the subcontinent — bringing sustenance and driving glaciers and life down through thousands of kilometres into all corners of the Indian Ocean, the Arabian Sea, the Andaman Sea, artists are drawn to the stories of water in their South Asian present.

Curator Zahra Khan chose Naiza Khan to represent Pakistan at the Venice Biennale in 2019. Together they showcased Manora Field Notes, a subtle and beautiful ode to Manora Island, off the coast of Karachi and in the Arabian Sea — a tiny fishing village presented as a microcosm of the country’s history — of which water, the politics of it, the impact of climate change all figure deeply in their central narrative.

The poet and art critic Himali Singh Soin grew up in Sikkim surrounded by mountains and has been drawn to the representation of time through the lens of the continuously shifting and increasingly vulnerable landscape and ecosystems of the Himalayas. Singh Soin has gone deep on issues of water and the melting polar ice caps, winning the 2019 Frieze artists awards for her research proposal on remote areas of the Arctic and Antarctic circles, building a complex narrative on a melting fossil — ice — that has witnessed historic changes throughout time. And Murree resident Saba Khan tells me about Pak Khawateen Painting Club (translated from the Urdu as Pure Pakistani Women’s Painting Club).

The Khawateen are a group of women artists who venture to the frontier of the Indus river for plein air painting of nationalistic infrastructure projects. These include mega hydropower dams in the country’s vulnerable northern areas and barrages in the poor south. In their own words stereotyped “as a benign, bourgeois group of patriotic conformists”, these female artists wear uniforms inspired by Pierre Cardin’s 1960s design for Pakistan International Airlines’ air hostesses and interrogate sites built by powerful men to generate power and energy for the country — subverting those very prescribed roles.

Architecture and sustainability

For architects across the subcontinent, commentary has been turned into action. Karachi based professional architects Tariq Alexander Qaiser and Marvi Mazhar have done extensive research and documentation on Karachi’s mangroves – part of an ecosystem that stretches between Mumbai, Karachi and along the coastline of Iran.

The two worked together on the Mangrove Project, documenting the destruction of this necessary ecosystem as part of the KarachI Biennial in 2019 titled.

Incorporating mixed media and soon to be borne out in the form of a documentary film by Qaiser, “Flight Interrupted: Eco Leaks from the Invasion Desk” considers how Karachi’s toxic environmental crisis has stagnated ecological relationships between her land, waters, and citizens. Both Mazhar and Naiza Khan are students of the deeply political forensic architecture program at Goldsmiths College in London.

The program was founded by a team of architects who decided to use their training to explore space to expose war crimes and social injustice — rooted through the lens of mostly violent countries — Palestine, Turkey, Minneapolis. Activism is at the core of their study. Certainly other practitioners are questioning the making in their own practice, Singh Soin works to minimise the carbon footprint of her work and output.

Bangladeshi architect Marina Tabassum was listed earlier this year by Prospect Magazine as one of the greatest thinkers for the Covid-19 era, “at the forefront of creating buildings in tune with their natural environments. Tabassum’s practice is built around local materials, sustainable practices and working with communities to consider nature and the environment; she recently unveiled designs for lightweight houses made from locally-sourced materials that perch on stilts and can be moved when the waters rise during Bangladesh’s now regularly occurring devastating floods.

And the celebrated architect and activist Yasmeen Lari has now for decades explored the use of sustainable design and construction techniques in her native Sindh, designing adobe style refugee housing for earthquake victims in Kashmir in 2015 and propagating the mud chulha to bring independence for women and sustainable material usage to homes in rural Sindh. Lari recently won the Jane Drew Prize for women in architecture — an award previously reserved, it was felt, for those who built more, better, higher.

Where are we going next?

The idea of less, of holding back, of creating space seems more salient than ever. Not just for how and why and where we build, but equally for how we live and begin to treat one another. In a world going online, with borders feeling more penetrating than ever before, location matters. Zain Masud, curator of the 2019 Serendipity Arts Festival in Goa, is one of many who continue to interrogate why and how art is placed in the context of history, climate, community.

In an era of social justice movements, pandemics, and an almost complete loss of control on the next 12 months of our world, surely “art” should mean something to the places in which it is being physically situated and displayed. Leaning into the lessons these designers, thinkers, philosophers are bringing to the fore will serve us all well as we sit at the edges of a hazy and parched (or even possibly submerged) future.

Suhair Khan works for Google and is currently based in London. Her work has mostly focused on the intersection of technology, creativity, culture and (recently) sustainability. She’s a visiting lecturer at the Architectural Association in London and founder of the Open/Ended design residency. Edited by Ambika Hiranandani