“No one is safe, until everyone is safe”

The second wave’s impact on India has been like no other, with people dying due to lack of oxygen and hospital beds. India has suffered a double whammy of lethal second waive caused mainly by the Indian variant and the UK variant as well as the horrid management by the government.

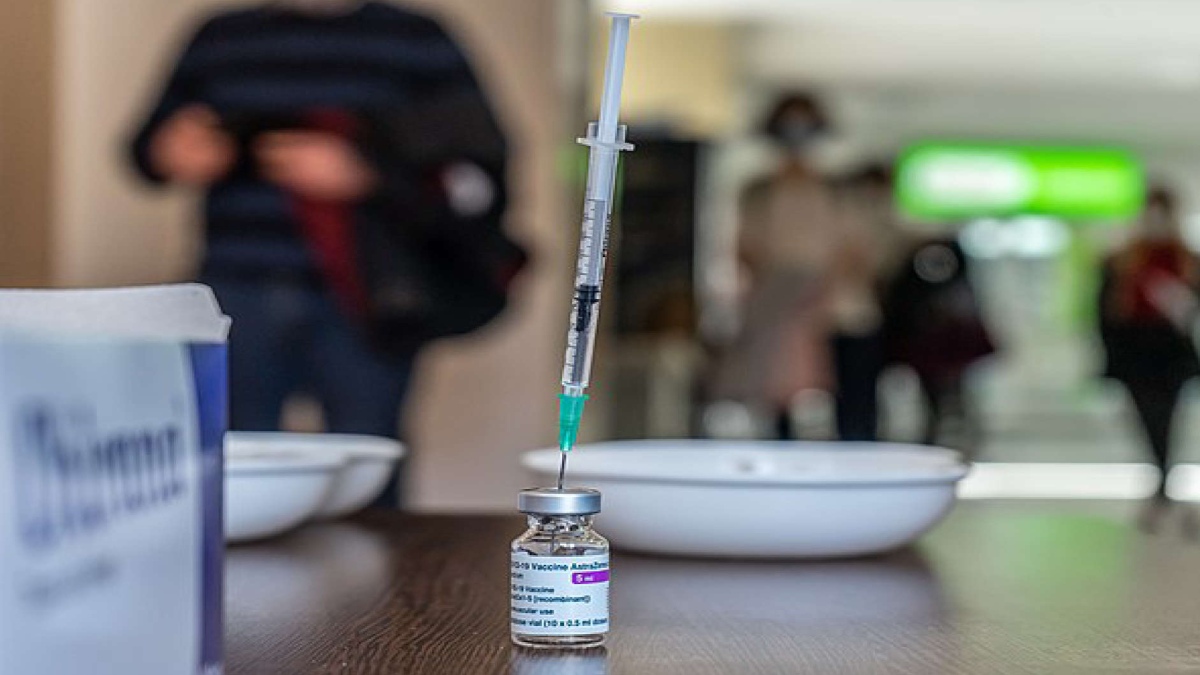

The Principal scientific advisor to the Prime Minister has called out the possibility of a third wave, which could be more menacing than the previous waves. While the lack of hospital beds, oxygen cylinders and key medicines such as Remdesivir exposed India’s lack of preparedness for the second wave, it is believed that vaccines are the only way out, if India is to avoid the subsequent wave(s). As of April 30, 2% of Indians have been administered with both doses of vaccine with 12.5 crore people taking the first dose. At this pace it would take 2 years and 9 months to completely vaccinate the whole country.

However, the rich countries such as the US, UK, EU, and Canada, which hold just 14% of the worlds’ population have usurped 53% of the eight most potent vaccines. A whopping 67 low income countries haven’t bought any vaccine and are solely relied on the COVAX initiative, which has secured approximately 700 million doses just enough to immunize 10% of the people in those 67 countries. These rich countries are also being accused of hoarding the vaccines.

This inequality in relation to the distribution of vaccines as well as the carnage that numerous waves of COVID-19 have caused in different countries has prompted a debate whether there can be a waiver of the intellectual property of the vaccines which could enable the lower income countries to take the formula of the vaccines and produce it in their countries. The author through this article seeks to analyse the possibility of IPR waiver, as proposed by India and South Africa. Moreover, the author would also analyse the possibility of using compulsory licensing to increase vaccine production in the country.

WHAT IS THE PROPOSAL?

An obvious inequality exists in terms of distribution of the vaccine all across the world with the developed countries usurping the greater share. A mere 0.3% of the total doses of the vaccine have reached the Low income countries. To tackle this situation, India and South Africa have submitted a proposal for waiving patent on drugs, vaccine and other medical products pertaining to COVID – 19 at the WTO. For this, they are seeking a waiver on the enforcement, application and implementation of sections 1 (on copyright and related rights), section 4 (industrial designs), section 5 (patents) and section 7(protection of undisclosed information) of part II of the TRIPS proposal pertaining to the containment, treatment and prevention of COVID – 19.

Moreover, a demand of a three years waiver has been made along with the components or the materials and methods which may be required in the production. The proposal would need the support of three – fourth of 164 members. At the moment, it has got the support of 120 countries along with the US, China and Russia which is a major boost.

The proposal has emphasised on the concerns regarding affordable, adequate and prompt availability of quintessential medical products and role of patents in hindering the manufacturing of these product and consequently affecting the accessibility to these products. Moreover, another primary reason of the proposal is the cumbersome processes required for import and exports of pharmaceutical goods under Article 31bis which provides the legal basis for members to grant special compulsory licenses exclusively for the production and export of affordable generic medicines to other members which cannot domestically produce the needed medicines in sufficient quantities. The bottom-line is that the provisions have been utilized just once since its introduction due to its complex and cumbersome requirement.

IS THE PROPOSAL TO REMOVE PATENTS A GOOD IDEA?

There is a cleavage of opinion on the suggestion of IPR waiver on vaccines. Developed countries as well as Pharma companies suggest that patents form an incentive for inventors to continue their work and to excel. Moreover, they raise concern on the notion of transfer of technology of these vaccines which involve complex methodologies, as to how would that work out. Whereas, the WHO and other developing and low – incoming countries cite a public health crisis which is causing carnage in different countries and suggest that the logic behind the use of patents on these essential medical products are difficult to defend in these testing times.

Questions have been raised with regards to the legality of a request of a waiver under the TRIPS agreement. Clause 3 and 4 of Article IX of the Marrakesh Agreements establishing the WTO, answer those questions. It asserts the possibility of a waiver from certain obligation under WTO treaties, such as TRIPS, in exceptional circumstance, and that it can be decided at a WTO ministerial conference. The Waiver proposal must justify the exceptional circumstances, all the terms and conditions and the time when the waiver terminates. And it is a fact that a pandemic would qualify as an exceptional circumstance. So, the merit of the proposal can’t be called into question.

HAS A PATENT BEEN WAIVED IN THE PAST?

Their exist precedents of a waiver of certain obligation under TRIPS. For example, a consensus was formed by the WTO members in 2003 for a waiver pertaining to paragraph 6 of the Doha declaration on the TRIPS agreement and Public Health. The waiver established a framework of compulsory license to allow countries producing generic medicines to supply the medicines to countries which couldn’t manufacture the medicine themselves.

In another instance, due to patent monopolies, the cost of drugs to be used by one patient for a year suffering from HIV/AIDS was over $10,000 twenty years ago. A Lot of people died because of inaccessibility to affordable medicine. It took an access – to – medicines movement from patient activists, civil society and health rights groups from South Africa and other countries of the world, who stood up to the Pharmaceutical companies as well as government inaction. Monopoly of companies on these drugs was removed, which fostered competition and generic production. It showed in results as the price of antiretroviral drugs dropped by 99% in the next decade, which ultimately helped solve the problem called HIV.

Looking at the example of South Africa and its long drawn battle with HIV, it can be concluded that the IP barrier definitely elongated that fight and was proving out be a hindrance to the accessibility to theses medicines at an affordable price. In the current scenario, as we are facing acute vaccine shortage, IP barriers would certainly elongate the fight against COVID – 19, which would be detrimental to the whole world including the developed countries.

The meeting of TRIPS council will take place on June 8 and if the waiver comes through, it will only be post-June. This coupled with all the bottlenecks related to production capacity of the vaccines, distribution and production of raw materials and components of vaccine are not going to be a quick fix. So the waiver won’t be the answer to our instant problem. But it would certainly help India and those low income countries in the long run.

IS COMPULSORY LICENSING AN ANSWER TO THE VACCINE SHORTAGE WOES?

India is the third largest manufacturer of pharmaceutical products in the world in terms of volume and 14th largest in terms of value, with a contribution of 3.5% of the total medicines and drugs exported globally. So, far, we haven’t been able to harness this pharmaceutical prowess to deal with this pandemic. Compulsory licensing might be that tool to achieve this goal.

The Provisions regarding Compulsory Licensing have been provided under Chapter XVI of the Patent Act, 1970. The Act lays down the criteria, which need to be fulfilled for granting a compulsory license under section 84 and 92. Compulsory licensing is the process of issuing licenses to a patent from the government without a requirement of the approval of the patent holder due to some predisposing extraneous situation, like a pandemic. Following an application, it can be granted to any interested person after the expiry of three years from the date of the patent. Moreover, section 84 lays down the ground under which compulsory license can be granted. The first ground describes that the patented invention hasn’t been able to satiate the reasonable requirements of the public. Secondly, the patented invention is not accessible to the public at an affordable price. Lastly, the patented invention is not worked in the territory of India.

Section 92 of the Act provides that if the central government is satisfied, in cases of extreme urgency such as national emergency or public non – commercial use, may at any time after sealing of the patent, grant compulsory license of that patent to any interested person. Moreover, the procedure laid down under section 87 which lays down detailed procedure for granting of compulsory license maybe skipped in the case of a public health emergency or an epidemic. The Doha Declaration also mandates and supports the use of Compulsory Licensing for countries that are facing tumultuous situations and need a hand.

However, we must examine if compulsory license will solve the interim shortage of vaccines that India is facing at the moment. The granting of compulsory licensing would certainly help overcome the restrictions imposed by the patent law, however, it would not help in transferring the know – how pertaining to the manufacturing of the vaccine. The production of vaccine requires techniques which are very advanced. The issuance of compulsory licensing does not create an obligation to share these techniques.

A solution to the aforementioned problem could be granting compulsory licenses of the Covaxin as it has been produced jointly by ICMR and Bharat Biotech, coupled with all the money that has been put in by the govt., the IP of Covaxin certainly rests with the government. However, this comes in with its own caveat as the production of this vaccine requires a ‘Biosafety level-3’ production facility, which would require at least a year to build. Hence, compulsory licensing won’t solve the vaccine shortage we are facing at the moment, but is a more long term solution which would require time and effort.

CONCLUSION

The passage of the proposal for TRIPS waiver or granting compulsory licensing with an aim to ramp up production would require time and patience and neither of them would provide a straightjacket and instant solution.

The situation we are in requires quick decision making. Increased delay would give the virus another chance to mutate and make its way to developed countries which are hoarding vaccines. Canada has enough vaccine to inoculate its citizens 10 times over; Britain could inoculate its citizen 8 times over. The first and foremost step that the developed countries could take is to stop hoarding of vaccine and donate the excess to the COVAX initiative, which would make sure equitable distribution of vaccine among the lower income countries.

Secondly, India could also explore the option of Voluntary Licensing. Voluntary licensing involves a process in which the patent holder authorises a third party to produce and sell the patented product on terms and conditions that benefit them both. Again Covaxin could make the best candidate with the possibly, the IP of the vaccine resting with the government. So far, the government has been reluctant to license the covaxin to possible producers and scale up its production. One could argue that this decision contradicts government proposal of TRIPS waiver for vaccine.

India could have augmented the production of Covaxin by urgently licensing it to as many pharmaceutical companies as possible. Increased production would have not only solved India’s woes, but also those low – income developing countries. This could demonstrate India’s strong political will to increase the accessibility of vaccines on a global stage.