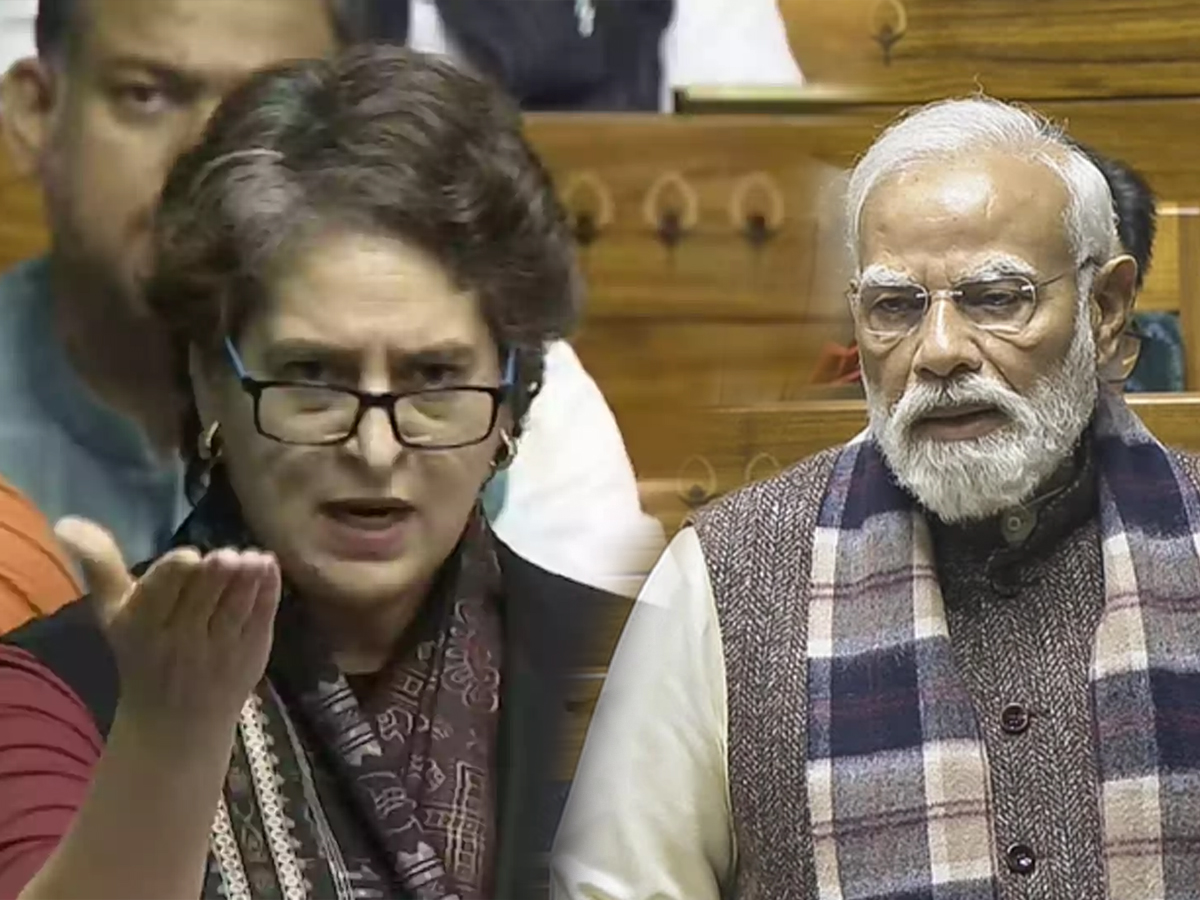

The Parliament’s heated Vande Mataram debate took a surprising historical turn on Monday. While opening the discussion, Prime Minister Narendra Modi cited a 1937 letter by Jawaharlal Nehru to claim that even Nehru admitted the song’s original context “could irritate Muslims.” Soon after, Priyanka Gandhi challenged the narrative. She quoted other passages from the same letter showing Nehru blamed the “present outcry” on communal forces, not on genuine Muslim objections.

Her challenge forced many lawmakers and observers to re-examine the letter’s full content and reconsider the familiar story of how Vande Mataram became controversial.

What Modi Highlighted in Parliament

Modi referred to Nehru’s 20 October 1937 letter to Subhas Chandra Bose in which Nehru admitted, “It does seem that this background is likely to irritate the Muslims.” He used this line to argue that the song’s critics had a point back then, implying that its controversy dates to independence-era communal tensions.

“The Muslim League’s politics of opposition to Vande Mataram was intensifying, and Mohammed Ali Jinnah raised a slogan against Vande Mataram from Lucknow on October 15, 1937… Just five days after Jinnah’s opposition, Nehru wrote a letter to Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, agreeing with Jinnah’s sentiment and stating that the ‘Anandamath’ background of Vande Mataram could Irritate Muslims,” Modi said.

Priyanka Gandhi’s Crucial Rebuttal

Priyanka Gandhi responded by reading out a fuller excerpt, “There is no doubt that the present outcry against Bande Mataram is to a large extent a manufactured one by the communalists.”

She emphasised that Nehru clearly placed blame on communal agitators, not on ordinary Muslims who may have felt uncomfortable. According to her, the original debate around Vande Mataram was less about religious sensitivity and more about political agitation.

This broader context challenges the version of history Modi presented, and pushes the debate back to where it started: communal politics, not cultural discomfort.

The Letter’s Full Message — Nehru, Bose, and the Muslim League

In 1937, Nehru wrote to Bose after listening to concerns over the use of Vande Mataram in public gatherings. He worried that its origins in the novel Anandamath might alienate Muslims. But Nehru didn’t stop there. He urged his party to bring Muslims into the fold to counter divisive forces. He also criticised the communal politics of the Muslim League, calling its recent actions a sign of “low type of communalism.”

In his words, “if we are unable to do so, they will strengthen the communal elements.” The letter tried to show that the song’s controversy was not inevitable, the communalists made it so.

Why This Matters Today — History, Identity, and Politics

- New history for old debates: The fuller letter forces reinterpretation of Vande Mataram’s journey, from national song to contested symbol.

- Political rewriting under scrutiny: Modi’s selective quoting triggered backlash, showing how historical texts can be used or misused in present-day politics.

- Communalism vs national identity: The debate reveals how cultural symbols get entangled in communal narratives, a cycle that began decades ago and continues now.

- Lessons for lawmakers: Quotes from history matter, but showing them fully matters more.

What Happens Next — Public Reaction & Historical Reassessment

Priyanka’s rebuttal gained immediate attention on social media and among historians. Many asked for the full 1937 letter to be made public. Some urged political parties to focus on unity rather than symbols. Others said this episode demonstrates how sensitive cultural symbols can be twisted for political ends.

For now, one thing’s clear: the Vande Mataram debate has shifted — from song versus sentiment to truth versus selective memory.