For many commentators, it has become a fashion these days to criticize India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru for keeping the Kashmir question alive and Sheikh Abdullah for harbouring secessionist tendencies. But looking at historical records and events that were taking place on the ground, it is safe to conclude that the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, which had a 75% Muslim population came to India only because of Nehru’s shrewd antics supported by popular leader Abdullah and in addition, because of the valour of Indian army.

As the lapse of British paramountcy approached, the Indian National Congress accepted the right of the states to join one or the other dominion as undisputed, only objecting to the possibility of independence for the princely dominions. The prospect of several of these states remaining independent after all created the very real possibility of the “balkanization” of India, a concern shared by the British as well.

About Kashmir, in particular, Nehru’s advice to the Maharaja Hari Singh, who harboured dreams of remaining independent would only be that independence for the state was unwise because “in the world today such small independent entities have no

Place.”

Barring Nehru, almost all had agreed that an outcome where Kashmir acceded to Pakistan was preferable to the Maharaja allowing paramountcy to lapse, and pushing the fate of the state into a dangerous limbo. Accordingly, given the Maharaja’s apparent inclination toward independence, Mountbatten attempted to convince him otherwise, while conveying an assurance from Patel that “if Kashmir decided to accede to Pakistan, we will be perfectly friendly about it.

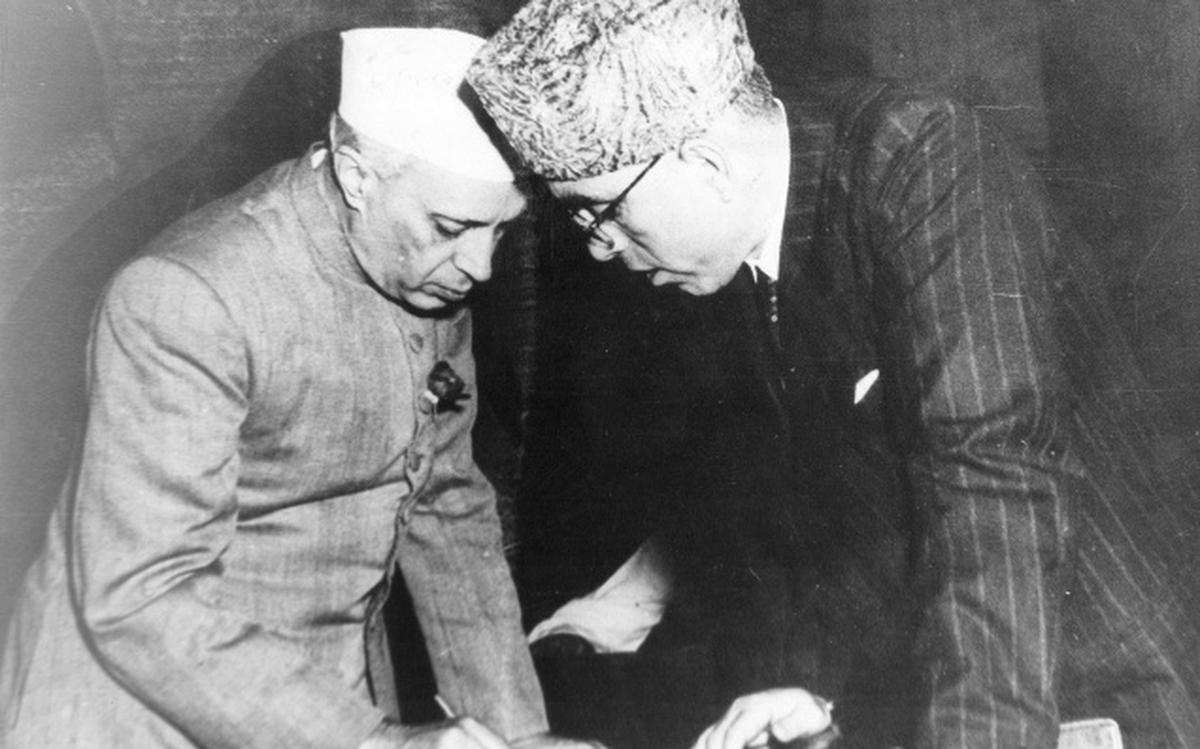

Author and bureaucrat Ashok Parthasarthi in his book titled GP:1915-1995 based on the notes of G. Parthasarathi—the multifaceted diplomat and policy advisor to Mrs Indira Gandhi, mentions that Nehru had sent his grandfather Sir Gopalaswami Ayyangar to Srinagar on September 23, 1947, on a secret mission. Ayyangar remained prime minister of Kashmir between 1937-43. He had successfully persuaded the Dogra King Hari Singh to accede to India—reversing the familiar theory that the invasion of Pakistan raiders had only forced the King to sign the Instrument of Accession.

Indeed, even as the Maharaja gradually began gravitating towards joining India, as convinced by Ayyangar at the behest of Nehru and then as a result of desperation as his forces were defeated by the Pakistan-backed tribal invasion, which commenced on October 22, 1947. Nehru was firm—that accession had to be seen to emanate from the people of Kashmir, and

therefore, required substantial political reforms and concessions to the popular leader Sheikh Abdullah and his National Conference party.

Those commentators, criticizing Nehru discount the fact that the state had 75% and Kashmir Valley had a 96% Muslim population. If Nehru through Sheikh Abdullah had not amassed public support, it was not possible for the Indian army even to land in Srinagar, leave alone conduct operations.

Pakistan Governor General Mohammad Ali Jinnah had sent his private secretary Khurshid Hasan Khurshid to Srinagar to assure the Maharaja about signing an instrument of accession with Pakistan.

Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi wanted Kashmir to join India. Nehru’s Kashmiri roots and friendship with Sheikh Abdullah made him push for it. According to historian Rajmohan Gandhi: “Vallabhbhai (Patel)’s lukewarmness about Kashmir had lasted until September 13, 1947.” In a letter that morning to Baldev Singh, India’s first defence minister, Patel had indicated that ‘if (Kashmir) decides to join the other Dominion”, he would accept the fact.

One cannot also shut eyes to the rebellion that had taken place in Poonch. In June 1947, about 60,000 ex-army men (mostly from Poonch) had started a no-tax campaign against the Maharaja. The campaign later turned into a secessionist movement following 14 and 15 August, when Poonch Muslims hoisted Pakistani flags. The Maharaja imposed martial law in Poonch, which further angered the Muslims there. With ammunition and personal support provided by the tribals of Pakistan’s NWFP, the situation got more complex, according to Victoria Schofield’s book Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War.

On 4 September 1947, General Henry Lawrence Scott, commander of the Jammu and Kashmir state forces, complained about multiple covert incursions from Pakistan and asked Maharaja’s government to raise this issue with Pakistan. The same day, J&K PM Janak Singh officially complained to Pakistan and asked for “prompt actions”. Meanwhile, Pakistan also levelled similar charges on the Jammu and Kashmir administrations, about incursions by Jammu Hindus into Sialkot.

Weary of all this, Maharaja Hari Singh released Sheikh Abdullah, who, in his first very first public meeting, reiterated that “the demand of the Kashmiri is freedom”. He also took a jibe at Jinnah, saying: “How can Mr Jinnah or the Muslim League tell us to accede to Pakistan? They have always opposed us in every struggle. Even in our present struggle (Quit Kashmir), he (Jinnah) carried on propaganda against us and went on to say that there is no struggle of any kind in the state. He even called us goondas.”

In early October, the Maharaja complained to Pakistan’s foreign ministry about the infiltration by tribals hundreds of kilometres inside the border in the Jammu region. Pakistan denied the allegation, but called the Maharaja’s attention to “terror and atrocities perpetrated by J&K forces against the Muslim population of Poonch” — atrocities which, it suggested, were provoking “spontaneous reactions both within J&K and from ethnic and religious kin across the border”.

Not much is known about the violence in Jammu and Poonch at this time, except for a couple of reports in British publications The Times and The Spectator. The Times stated: “2,37,000 Muslims were systematically exterminated — unless they escaped to Pakistan along the border — by the forces of the Dogra State headed by the Maharaja in person and aided by Hindus and Sikhs.”

A young lawyer and landowner from Poonch, Sardar Ibrahim Khan, a member of the Jammu & Kashmir Legislature who had been a legal officer under the Maharaja, emerged as the head of the Poonch liberation movement. He united the different factions in Poonch and held contact with some of the key figures of Pakistan’s Muslim League, including prime minister Liaquat Ali Khan. He was instrumental in establishing an “Azad Kashmir” government in Rawalpindi.

As relations froze, Pakistan suspected that Maharaja Hari Singh would accede to India. Also, given Sheikh Abdullah’s animosity towards the Muslim League, Pakistan decided to seize Kashmir by force. Pakistan launched ‘Operation Gulmarg’ by mobilising tribals from the NWFP on 22 October 1947. About 2,000 tribesmen, fully armed with modern weapons and under the direct control of Pakistan Army generals, entered Muzaffarabad on motor buses and foot. As the invaders captured Uri and Baramulla with minimal resistance from the Maharaja’s forces, the fall of Srinagar looked imminent. On 24 October, Maharaja Hari Singh appealed to India for military assistance to stop the aggression.

The request was considered on 25 October in a meeting of India’s Defence Committee, headed by Mountbatten and including Nehru, Patel, Baldev Singh, minister without portfolio Gopalaswami Ayyangar, and the British commanders-in-chief of the army, air force and navy. The committee concluded that “the most immediate necessity was to rush arms and ammunition already requested by the Kashmir government, which would enable the local populace in Srinagar to put up some defence against the raiders”, according to Lt Gen. K.K. Nanda’s book War with No Gains.

Besides the India army’s valour, it was the local support garnered by Sheikh Abdullah against riders that played a large part. One of the disciples of Abdullah, Maqbool Sherwani, the man from Baramulla, changed the course of the 1947 India-Pakistan War. He was killed on November 7, 1947, by tribal invaders.

Born in a Baramulla family that owned a small soap factory, Sherwani right since his adolescence was associated with political activities in the region and joined National Conference (NC) in 1939. Sherwani was part of the 22 National Conference volunteers who joined the resistance forces of the national militia and led several detachments of militiamen who toured different areas instilling confidence and unity among the terror-stricken people of Kashmir. He along with other volunteers worked as guides at vital installations to keep track of the mercenaries.

To frustrate the raiders’ advance towards Srinagar, he misinformed them, diverted them, and made them wander in the Sumbal area on the wrong routes. His display of presence of mind exhausted their precious time till the troops of the Sikh Regiment of the Indian Army reached Srinagar for its defence. After realising that they were being misguided, the raiders crucified him in the central square of Baramulla. Courage with which he sought to impede the advance of the tribals and he gave the crucial time of four days to the Indian army to land and build logistics.

Having accepted the instrument of accession, moreover, Mountbatten immediately informed the Maharaja that “in consistence with their policy that in the case of any state where the issue of accession has been the subject of dispute, the question of accession should be decided in accordance with the wishes of the people of the state, it is my government’s wish that as soon as law and order have been restored in Kashmir and her soil cleared of the invader the question of the state’s accession should be settled by a reference to the people.”

It was necessary to keep Abdullah in good humour till India could build up its hold and also the West, which was siding with Pakistan. That Nehru was not keen on holding a ‘fair and impartial plebiscite, despite his formal commitment to it, became clear as early as December 1948. When Indira Gandhi’s letter to her father written from Sonemarg on 14 May 1948 mentioned that in Kashmir only Sheikh Abdullah felt confident of winning the plebiscite and argued that mere political talks would not suffice; Nehru wrote back that this talk of the plebiscite was meant to keep world powers in good humour.

When Abdullah insisted on his promise, he did not hesitate to put his friend behind bars in August 1953, thereby foreclosing the possibility of Kashmir’s secession from India, while at the same time trying to wipe out the State’s “Special status”.

Over time, a plebiscite in Kashmir, no matter what the UN might resolve, made the implementation of the plebiscite more and more difficult. In fact, Nehru had been thinking of settling the Kashmir issue on the principle of accepting the status quo, with rectifications of the border that would satisfy both India and Pakistan. He mentioned this during meetings with Pakistan Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Bogra and Interior Minister General Iskandar Mirza in May 1955, and even earlier, during his two meetings with Liaquat Ali Khan in 1948. But for obvious reasons, they did not agree. In February 1954, the J&K Constituent Assembly, while adhering to the special position of the State, passed a resolution confirming the legality of Kashmir’s accession to India.

By October 1956, it had adopted a Constitution for the State which became operational on 26 January 1957. It provided for the jurisdiction in the state of the Indian Supreme Court and the Comptroller and Auditor General and declared that the State of Jammu and Kashmir ‘is and shall be an integral part of the Union of India’, despite protests by Sheikh Abdullah from his prison cell, and the UN Security Council.

Sheikh Abdullah was interred again from 1965-68 and the Plebiscite Front was banned, to prevent it from participating in the elections in Kashmir. Finally, the Sheikh was exiled from Kashmir during 1971-72. The India-Pakistan war and the liberation of Bangladesh brought about a significant change in Sheikh Abdullah’s attitude; he no longer talked about a plebiscite for settling Kashmir’s future.

An opportunity came in 1975 through the signing of the Indira Gandhi-Sheikh Abdullah Agreement. He agreed to accept Jammu and Kashmir as an integral part of India by getting a resolution passed by the State Assembly on the condition that all the Acts and Ordinances issued by New Delhi since 1953 would be reviewed. Sheikh Abdullah returned to power as the Chief Minister in 1975. But the agreement was never placed before Parliament, nor did the promised review take place.

The hatred of Nehru has been fuelled by falsehoods of history. If Kashmir is a part of India, it is almost entirely because of Nehru. He had the foresight to forge an understanding with its tallest leader, Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah in the 1930s. As far back as in May 1947, he wrote a detailed memorandum to the Viceroy Mountbatten staking a claim to Jammu and Kashmir ahead of the Partition.

There is also opposition to Nehru for ageing to a ceasefire. This is utterly and totally false. Volume 1 of Patel’s correspondence belies the charge that Patel was not taken into confidence. In that event, he was man enough to resign from the cabinet. The record was set out in full by a professional military historian, S.N. Prasad, based on interviews and official records. He was the director of, the historical section of the Ministry of Defence. History of Operations in Jammu & Kashmir (1947-48) was published in 1987 by the history section of the defence ministry.

The enemy had in December 1948 two infantry divisions of the regular Pakistan Army, and one infantry division of the so-called ‘Azad Kashmir Army’ fighting in the theatre. These comprised fourteen infantry brigades; or 23 infantry battalions of the Pakistan Army and 40 infantry battalions of “Azad Kashmir”, besides 19000 Scouts and irregulars. Against this, the Indian Army had in J&K only two infantry divisions, comprising twelve infantry brigades; a total of some 50 infantry battalions of the regular army and the Indian States Forces, plus 12 battalions of the J&K Militia (some with only two companies) and 2 battalions of the East Punjab Militia.

It is clear that Indian forces were outnumbered by the enemy in J&K, and only the superior valour and skill, and perhaps fire-power, together with the invaluable help from the tiny Air Force, enabled the Indian Army to maintain its superiority on the battlefields.

At about the end of 1948, there were 127 infantry battalions of the Indian Army, including Parachute and Gorkha battalions and State Forces units serving with the Indian Army, but excluding Garrison battalions and companies. Of these 127, some fifty battalions were already in J&K. Twenty-nine battalions were in East Punjab, guarding the vital sector of the Indo-Pakistan frontier. Nineteen battalions were stationed in the Hyderabad area, where the Razakars still posed a potential threat to law and order and the Military Governor required strong forces at hand to complete his task of pacifying the area. There were thus only twenty-nine battalions, available for internal security, to guard the thousands of kilometres of the frontier, and to act as the general reserve.

By scraping the barrel, more forces could certainly be despatched to J&K. But this would have accentuated the supply problem, as the entire force in J&K had to be maintained by a single rail-head, and a single road. This road was long and weak and had numerous narrow bridges with which few liberties could be taken.

While logistics put a definite limit to the size of the forces that India could maintain in J&K. Pakistan suffered from no such limitation. There were numerous roads from Pakistan bases to the J & K border, and from there the actual front line was generally accessible by short tracks or roads. So there was no maintenance problem for whatever reinforcements Pakistan could send to her forces in J&K to block any Indian advance.

Given the military situation, a ceasefire was imperative. Had it not acted, Pakistan would have gone to the UN first, citing India as a respondent. In fact, the issue came up on December 8, 1947, in Lahore when Mountbatten and Nehru went there to meet Liaquat Ali Khan. What Nehru had done, was to preempt Pakistan from going to the UN. Had it gone, the UN Security Council would have adopted a resolution under a different chapter, that would have amounted to sending international troops to conduct a plebiscite. Those who have followed Gulf Wars and Afghanistan know that the UN could have mustered troops to take control of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, which would have been determinantal to the interests of India.