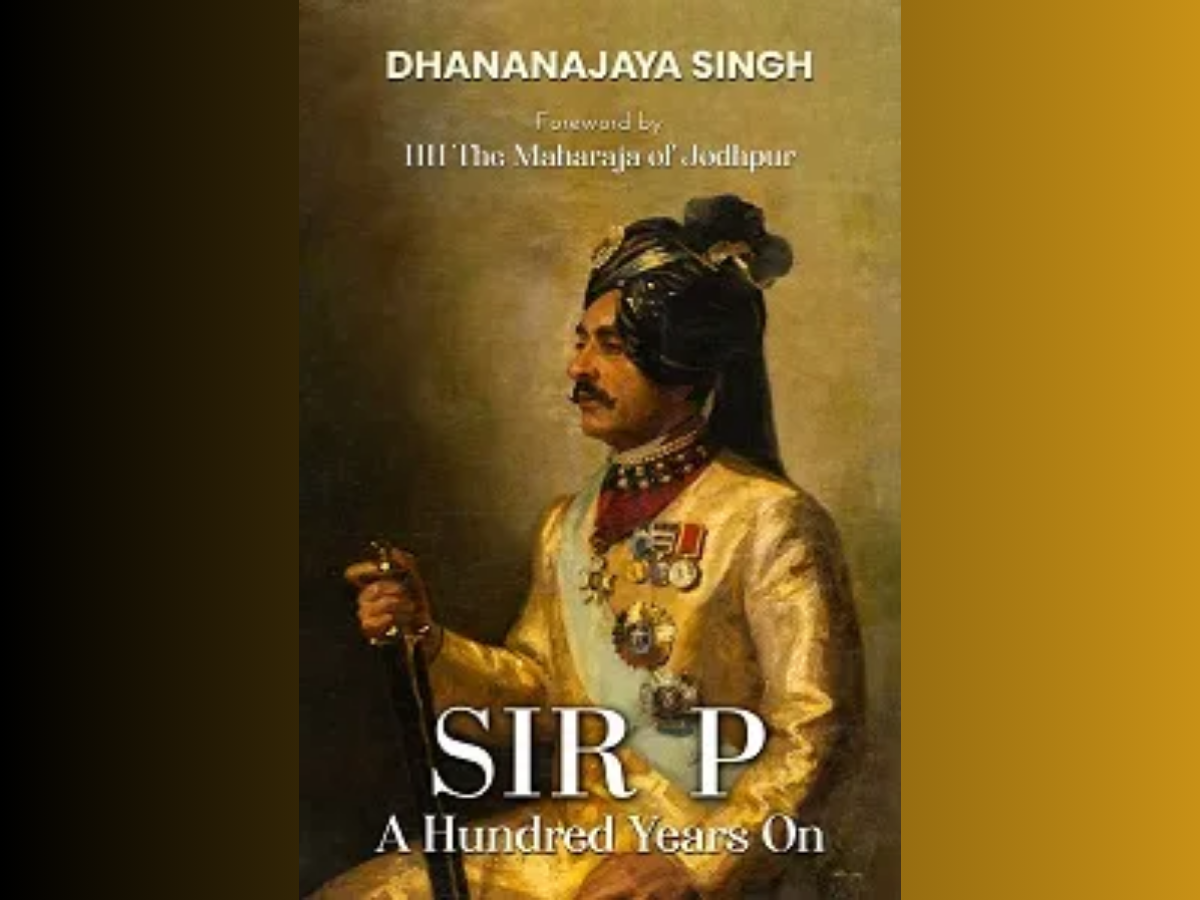

‘Sir P — A Hundred Years On’ is a book that celebrates the extraordinary but hitherto unsung life of Sir Pratap Singh of Jodhpur (1845- 1922). Better known as Sir P, he was the third son of Sir Takhat Singh, the then Maharaja of Jodhpur and carved a legacy for himself as an able administrator and an ace reformist, as a keen sportsman and a courageous soldier.

Within the Marwar region, much is known about the legendary Sir P as his life is woven into the region’s folklore; and yet little has been written about this modern Rajputana’s greatest son. That task was left to his great-great grandson and author, Dhananajaya Singh to pen down his definitive biography. It is a tale well told, woven with rich anecdotes and all the little nuggets that bring to life an entire era. But having read the book, what will stay with you is the author’s trademark wry humor and his eye for detail. (The St Stephen’s educated Cambridge Graduate, Dhananajaya Singh is also the author of the best-selling ‘The House of Marwar’, which came out in 1994)

The foreword has been written by Gaj Singh II, the titular Maharaja of Jodhpur who notes that Sir P was a “Soldier, statesman, social reformer, sportsman – an administrator in synchrony with both the Arya Samaj and Raj- we have all grown up with Sir P in Jodhpur. We owe him a debt and are still, in many ways, defined by his legacy.”

A sentiment that Dhananajaya takes forward in the pages of this well researched saga. Pratap Singh was the third son of the Maharaja Takhat Singh and can trace his lineage to the great Rana Pratap from his mother’s side. The fa ther had a special fondness for this plump little child calling him Shubhji Lal (auspicious child) and took over his care when little Pratap was just three years old, making him sleep next to him in the beautifully decorated Takhat Vilas high up in Mehrangarh’s Mardana appartments. As the author notes, the father enjoyed a far happier relationship with him than with his elder brothers Jaswant and Zoravar. In the midst of this family history, the author also adds an interesting nugget “Pratap, struggling with painful, perhaps preordained bow-legs (that came to be known as Jodhpur Legs), claims he `never crawled but went straight to walking with the help of a wooden horse with wheels’.” It is little details like this that help humanize a legend.

Dhananjay’s flair for the descriptive must be commended, as he delves into not just the archival history but also the anecdotal culture of folklore to tell of an era gone by. The chapter very aptly titled The Jaipur Intern tells us of the mentor like relationship that Pratap Singh had with his brother-in-law, the then Maharaja Ram Singh II of Jaipur (1835-80). There’s an interesting anecdote at the beginning of the chapter where the author describes the wedding celebrations.

As he writes, “Almost every Rajput clan has a story in its hoary past of an assassination or a blood-letting during celebrations and intoxicated bonhomie. This Is also why Rajput swords are tightly knotted with colourful scarves during wedding ceremonies, `We come in peace’.” Pratap went on to spend two years with his brother-in-law in the Pink City and it was here he picked up his administrative skills, not to mention his first sip of sweet Green Chartreuse

But he was soon called back home by his older brother with the royal version of an ‘Enough is Enough’ summons in 1878, where Pratap Singh served as the Regent (Prime Minister) in Maharaja Jaswant Singh’s court and spear headed many reforms in the Marwar region. The author notes that the then Maharaja Jaswant Singh was content to let Pratap Singh symbolise the “power, prestige and dynamism of the Government…Now was the legend of Sarkar Bapji born. Here, like Akbar the Great, descending incognito, after dark, into the Bhitri Shahar – the inner/walled city for a first-ear sense of his subjects. There, personally leading a posse on horse back at dawn in his relentless drive against dacoity.”

It wasn’t all work, for Pratap Singh found time to play as well. His polo team was the Indian champion in 1893 and became the first Indian team to play on British soil in 1897. Sir P is also credited for being the designer of the now famous Jodhpur Breeches.

What also stands out in the book is the way the author portrays the many layered relationship between the British Raj and the Indian princes with a nuanced pen. As Dhananajaya writes in the Author’s Note, “How was he, the Icon of the Raj also a pillar of the Arya Samaj? How could a Rajput Prince described as a beau ideal – the much favoured favourite of three British Monarchs – also be remembered as the first to ban foreign textiles in his country, fabric and costume, long before Gandhiji returned to India?”

The way the author tells it, this is the story of “an old-school Rathore Rajput Warrior from Marwar – the Land of Death – becoming a Man of the World, now marching up the Champs de Élysées in Paris, now mobbed on the Mall in London – the first Indian Celebrity to push Britain’s frosty glass door open.”

And adds, “The relationship between India’s Princes and the British Raj may have been complicated and unequal, often uncomfortable, sometimes humiliating – but it was also a wonderful, nuanced and multi-dimensional, subtle and mutually-productive partnership in so many ways.“ All this and more, comes to life in the story of Sir Pratap Singh, Marwar’s Renaissance Man. If you are either a student of history or a chronicler of the House of Marwar; or just a lover of a tale well told — then this book is a must read