This December is special to the armed forces and the nation as we commemorate the commencement of the fiftieth year of our victory in the 1971 India-Pakistan war. However, this should not obscure another significant military action in which the three services operated together and brought to a swift closure—the liberation of Goa, Daman and Diu. This year we step into the diamond jubilee or the sixtieth year of that action and that too needs celebration because with that we excised the last vestiges of colonial rule on the Indian subcontinent.

While India became independent in August 1947, the Portuguese enclaves of Goa, Daman and Diu continued as colonial entities. As India had got Independence through non-violent methods and as she had regained territories from the French peacefully, she sought to retrieve Goa, Daman and Diu in a similar manner. Hence, several attempts were made to resolve the issue through negotiations at bilateral and multilateral levels. However, not only was Portugal unyielding but it turned more repressive against freedom fighters and more recalcitrant at international forums. Finally, in 1961, the government decided to use military force as the last option.

On 18-19 December 1961, the Government of India executed Operation Vijay to liberate the Portuguese colonies in India. This was the first time in the history of independent India that all three services operated together, not taking into account the brief ‘Op Peace’ in Junagarh just after Independence. This was also the first time the Navy fired in anger. While the Army action has been extensively written about, that of the Navy has not been given adequate attention. This short article recounts the naval action and contribution during the Operation. Geographical contiguity and the need for boots on ground implied that the major component of the operation would be Army led, with the Navy and Air Force in a support role. Accordingly, by 11 December 1961, Indian forces were placed at Belgaum, Vapi and Una, for attacks on Goa, Daman and Diu, respectively.

The broad tasking for the Navy consisted of control of sea areas off, and seaward approaches to, the three territories, prevention of hostile action by Portuguese warships, shore bombardment using naval guns and search and strike through the Aircraft Carrier Air Wing. In addition, Navy was directed to capture Anjadip Island after the Army conveyed its inability to ‘provide troops trained in amphibious operations’. While the three territories were geographically dispersed, the centre of gravity was Goa given the concentration of force and Portuguese power there. Thus, the Navy’s operations off Goa were intended to secure access to Mormugao Harbour, to neutralise the coastal batteries, sink or immobilise Portuguese Navy ships there and to launch naval landing parties to take Anjadip.

A naval task force was formed with Rear Admiral BS Soman, the then Flag Officer Commanding Indian Fleet (FOCIF) as the Naval Theatre Commander. The force was divided into four task groups—the Surface Action Group comprising Indian Naval ships Mysore, Trishul, Betwa, Beas and Cauvery; the Carrier Task Group comprising IN ships Vikrant, Delhi, Kuthar, Kirpan, Khukri and Rajput; the Minesweeping Group comprising of minesweepers Karwar, Kakinada, Cannonore and Bimilipatan and finally the Support Group INS Dharini.

While this may seem like overkill, it needs to be noted that this catered for three dispersed sites. The concept of operations needed to cater for all possible threats. Since there was apprehension of the approaches to ports being mined and of possible presence of submarines, naval missions also included aerial surveillance, mine counter measures and anti-submarine measures. Further, initial intelligence indicated that the Portuguese had deployed four frigates. However, when action struck, only one frigate, the Afonso de Albuquerque was available for the naval defence of Goa, the other three having sailed earlier for Portugal.

Earlier, unprovoked firing by the Portuguese from Anjadip on Indian steam ship Sabarmati had injured her Chief Engineer, some fishermen and caused one fatality. To assure the fishermen and as a deterrent, destroyer INS Rajput and frigate INS Kirpan, were deployed off the Karwar coast, as early as 28 November 1961.

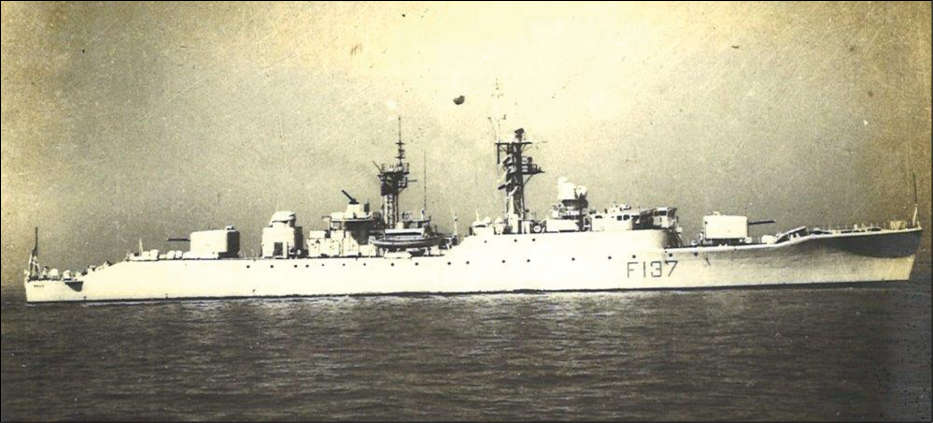

By 1 December 1961, foreseeing action, the Naval Headquarters executed surveillance and reconnaissance exercise, Operation Chutney. Two Leopard Class frigates, INS Betwa and INS Beas, commenced patrolling off the coast of Goa. This helped them keep a watchful eye on all ingress and egress – of shipping, aircraft and personnel—and to retaliate with necessary force, if engaged by the Portuguese units in the air or on the surface. The capture of Anjadip Island was entrusted to landing parties from INS Trishul with covering fire from INS Trishul and INS Mysore. The landing party members had been trained in Cochin from early November onwards without compromising on secrecy of the plan. INS Delhi was detached to provide support to the Army in Diu. INS Vikrant with a couple of escorts remained off Mumbai to respond to contingencies either south or north as required.

On the morning of 18 December, the Portuguese frigate Afonso de Albuquerque was anchored off Mormugao harbour. Besides engaging Indian naval units, the ship was also tasked with providing coastal artillery batteries to defend the harbour and providing radio communications with Lisbon as shore radio facilities had been destroyed in airstrikes conducted by the Indian Air Force earlier. Based on a signal by the Navy Chief, VAdm RD Katari which said “Capture me a Portuguese frigate please”, at about 12 noon on 18 December, the three Indian Frigates – Betwa, Beas and Cauvery—steamed into Mormugao harbour and fired on the Afonso with their 4.5 inch guns while transmitting directives to surrender, in Morse code, between shots. In response, the Afonso lifted anchor, headed out while mingling with merchant ships anchored in the harbour and returned fire with its 4.7 inch guns.

A few minutes into the exchange of fire, the Afonso took a direct hit on its gun director position, injuring its weapons officer and killing two sailors. With continuous gunfire from Indian ships the cloudburst of shrapnel exploded directly over the ship, severely injuring many personnel including its Commanding Officer, Captain António da Cunha Aragão, after which First Officer Pinto da Cruz took command of the vessel. The ship was now burning amidships and her propulsion system was badly damaged in this attack. The Afonso swerved 180 degrees, ran aground at Bambolim beach, where the crew abandoned

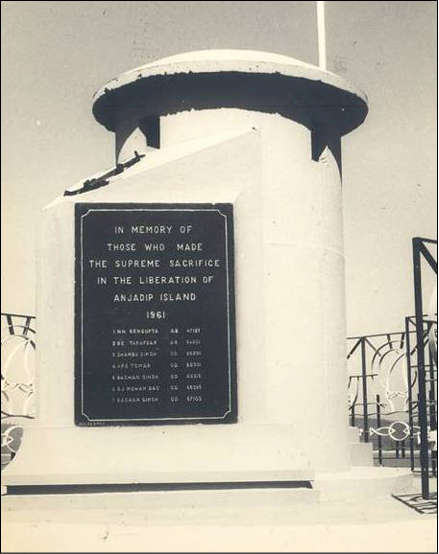

ship and she hoisted the white flag of surrender. The overall engagement lasted for about fifty minutes. Concurrently, in the early hours of 18 Nov, Anjadip Island was also stormed. In an act of perfidy, the Naval landing party, under the leadership of Lieutenant Arun Auditto, was duped by the display of a White flag of surrender by the Portuguese and then fired upon, causing seven deaths and wounding nineteen others. In a first person account Auditto, recollects in the book “Blueprint to Bluewater”, by Rear Admiral Satyindra Singh.

“I took charge of the first wave of the assault party and we went peacefully towards the beach and I began to believe that ‘surrender business’ was indeed true. We landed, took position and the boats were sent back to bring the second wave. Fifteen minute later, the second wave, under the command of Senior Commissioned Gunner N. Kelman, approached the beach at about 0745 hours. Suddenly all hell broke loose as sprays of machinegun bullets opened up on the boat from Portuguese gun-post on the south hill top. Kelman, with great presence of mind, continued towards the beach, zigzagging the boat to counter the gun fire. A few minutes later, by the time the boat beached, it had been riddled with bullets. Kelman had been wounded on both his thighs – fortunately only flesh wounds but all the same, seriously. However, owing to Auditto’s leadership and the courage shown by others, the landing operations were successfully carried out. Trishul used her gunfire to telling effect while Mysore provided an additional landing party. The first phase of the operation was completed on the early afternoon of 18 December 1961, while mopping up operations continued. Auditto, Kelman and others involved in the action were, subsequently, conferred gallantry awards. A memorial was later erected on Anjadip Island, to commemorate those who had made the supreme sacrifice.

Meanwhile off Diu, INS Delhi was deployed to provide ‘distant support’ to the Indian Army and directed to be ten miles clear of coast, keeping in mind ‘shore batteries, hostile aircraft, motor torpedo boats and possible submarine threat’. Capt N. Krishnan, its Commanding Officer, was not the sort who could be kept out of the fray in this manner. Early on the morning of 11 Dec 1961, after sinking two5 small enemy ships off the harbour, Delhi learnt that the Army troops were under very heavy and well directed fire from the Diu fortress and were unable to make progress. Krishnan quickly closed the ship to one mile from shore and undertook heavy bombardment—11 broadsides and 66 shells—of the fortress with the formidable 6 inch guns of INS Delhi.

Within 15 minutes of unleashing the devastating fire that destroyed the lighthouse within the fortress and other fortifications, the white flag of surrender had been hoisted and it was the Delhi’s boat with a young Sub Lieutenant Suresh Bandoola that hoisted our national colours in Diu for the first time. Krishnan’s action came in for huge praise from Lt Gen JN Choudhuri, the GOC-in-C Southern Army Command and overall in charge of Operation Vijay, who wrote to him later “I would particularly like to thank you for the help you gave while commanding INS Delhi. You really saved the situation”. In fact, since the Army did not move in until 19 Dec, Delhi patrolled the area and sustained the situation.

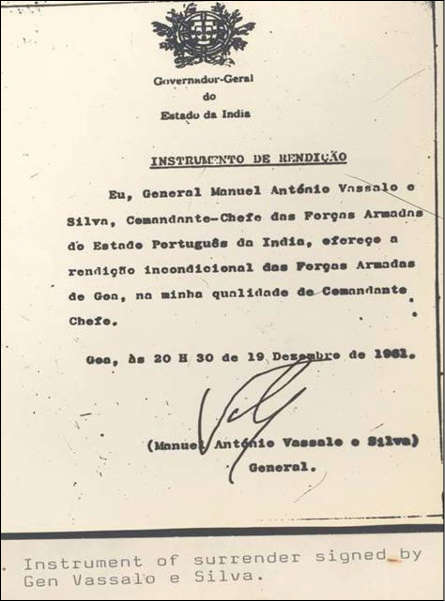

Following the indisposition of the Albuquerque, the Indian Navy continued patrolling till 19 December 1961 and thereafter ships were ordered to return to Bombay. All operations in Goa came to an end at 6:00 p.m. on 19 December 1961. The documents of surrender were signed by Portuguese Governor General, Vassalo De Silva at 8:30 p.m. and Major General (later Lieutenant General) K.P. Candeth was appointed as the Military Governor of Goa. Thus, within 40 hours of the start of the military operations, the centuriesold foreign domination in Goa came to an end, and the Indian Navy emerged victorious in its first action.

The overall ease and smoothness with which the Goa liberation operation was conducted, in part due to the tactical brilliance of Brig Sagat Singh on land, has led many to conclude that it was not much more than a police action and, therefore, this operation has not been given the attention it deserves in the annals of Indian military literature. Further, some scholars, like Prof G.V.C. Naidu, have concluded that the Navy’s role in this endeavour was minimal. However, there are many reasons why the operation in itself and the naval participation had much symbolic and substantive significance.

First, the first tri-service operation saw reasonably close coordination between all three services. Not only were the Force and Theatre Commanders on the same grid but other service representatives were embedded in sister service Tactical Headquarters for better coordination.

Second, India was taking on an erstwhile colonial power. While this resort to violence was deemed ‘uncharacteristic or hypocritical’ by many western commentators, it also sent a message of resolve in a situation where our nation was pushed to the wall. This was just a few years into a post-World War global order where winds of change were blowing but had still not completely displaced the colonial powers as a global elite. Portugal then had the support of the US, Britain and NATO.

Third, Portugal was the earliest colonial power in India and the Indian Ocean Region, having set up their enclave in Goa in 1510. Thus, their displacement 450 years later had a special historical significance.

Fourth, India had lost her independence due to its neglect of the oceans and a long phase of ‘sea-blindness’ which allowed colonial powers with superior maritime prowess to impose their will on land. Independent India using her Navy to exert force, even modestly, against the earliest colonial power, was a new paradigm, a sign of new dawn. The fact that the Portuguese ship which surrendered, Afonso de Albuquerque, was named after the very Governor who established Portuguese rule in India needs to be underscored for its very symbolic implication. Similarly, it was the naval Battle of Diu in 1509 which proved seminal in ushering Portuguese colonialism; thus, to use our navy there to write its epitaph with withering gunfire was deeply symbolic.

Fifth, it taught the Navy valuable lessons. The perfidy at Anjadip resulted in loss of lives and injury. While the men on ground showed great courage in land-fighting (which is not Navy’s domain) the need for focused strategizing, better communication, better intelligence, more preparation and lesser naiveté were hoisted and embedded in the naval psyche. The actions elsewhere, the baptism by fire, exposure to violence and the smell of cordite were necessary to ‘groom the Navy’ for future contingencies.

Sixth, it once again highlighted the importance of the maritime dimension, even where wars are continental in nature. By ensuring blockade of the three ports, the Navy ensured uninterrupted Army activity. If Portugal had brought in reinforcements or deployed more maritime forces, the Indian Navy was well placed to prevent that. The bombardment at Diu and the quick neutralising of Afonso, indicate the usefulness and flexibility provided by the maritime domain.

Seventh, the operation also showcased India’s softer, benign side. Rules of engagement were drawn to minimise casualties, captured prisoners were treated with courtesy and high calibre weapons were not used unless first fired upon. Despite this leading to certain tactical disadvantages, they were scrupulously adhered to. This contrasted with the barbaric way that Portugal dealt with Indians during its initial conquests and colonial rule. A telling illustration of this is in the manner that the skipper of Afonso de Albuquerque,Captain António da Cunha Aragão was treated in hospital with much care and visited by Commander RKS Gandhi and Commander T.J. Kunnenkeril. They both wished him well and gifted him chocolates, flowers and a bottle of brandy. These two gentlemen were the Captains of Betwa and Beas that had damaged Afonso.

Eighth, an anecdote that brings out, possibly, another lasting significance. Two years ago, we met at an official navy function, the Angolan Permanent Representative (PR) to the United Nations (UN). An Army General turned diplomat, this lady had also taken part in their liberation struggle. She said some of their liberation fighters had been in Goa, in December 1961, fighting on the Portuguese side. Their defeat then, ironically, led them to believe that their Colonial masters could indeed be overthrown. This provided inspiration for their Colonial struggle and freedom movement.

Ninth, the liberation realised the dream of all Indians, especially Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the great integrator of states, who in the Defence Committee of Cabinet meeting sought to know if the Fleet could push the Portuguese out. Further, when he embarked Delhi in April 1950 and sailed down the western coast, he wistfully wished that the Indian Navy would steam into Goa and take it.

Finally, the liberation of Goa provided the template and takeaways for future triservice operations. A decade later, many of those involved in Goa, were the heroes of 1971 war—Sagat Singh, Krishnan, R.K.S. Gandhi. Goa was like a trailer to the grand finale that was 1971. It took us just 40 hours to end 450 years of Portugal’s Asian empire. Dec 1961 was the dawn of a new era.

Cmde Srikant Kesnur and Lt Cdr Ankush Banerjee are serving naval officers, associated with the Naval History Project. Views expressed in this article are personal in nature.