In March 2020, as cases of COVID-19 began to rise in India, millions of schools across the country shut down, to protect young children and communities from the risk of infection. Today, about one and a half years later, most students continue to be confined to online schooling. Many from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, castes, communities, especially girls, have dropped out of school completely in disproportionate numbers.

According to data from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the duration of school closures in India has been the longest in the world. Parents with meagre incomes and vulnerable jobs have been forced to sacrifice their children’s education to make ends meet due to the financial impact of COVID-19 and the subsequent lockdowns.

The impact is greatest on children in low-resource settings who do not have access to remote learning tools and youngest children who are at key developmental stages. Children from rural areas face greater challenges when attempting to access online education, as only 47 percent of households in villages receive electricity for more than 12 hours a day. In rural India, the ASER (Rural) 2020 Wave I survey found, the proportion of “out of school children” has increased from 1.8 percent to 5.3 percent in the 6-10 age group between 2018-2020. Prolonged school closures have had an impact on the learning and development abilities of children, including on their physical and mental health. This disproportionately impacts children from marginalized groups and communities. While some states in the country have reopened schools on alternate days for those in Classes XI and XII, the majority of children continue to be subjected to the online learning mechanism. Though the government has prioritised the reopening of non-essential economic activities such as malls, including sporting and political events, the reopening of schools seems to be much lower down on its list of priorities.

THE UNEQUAL IMPACT OF ONLINE EDUCATION ON MARGINALISED COMMUNITIES

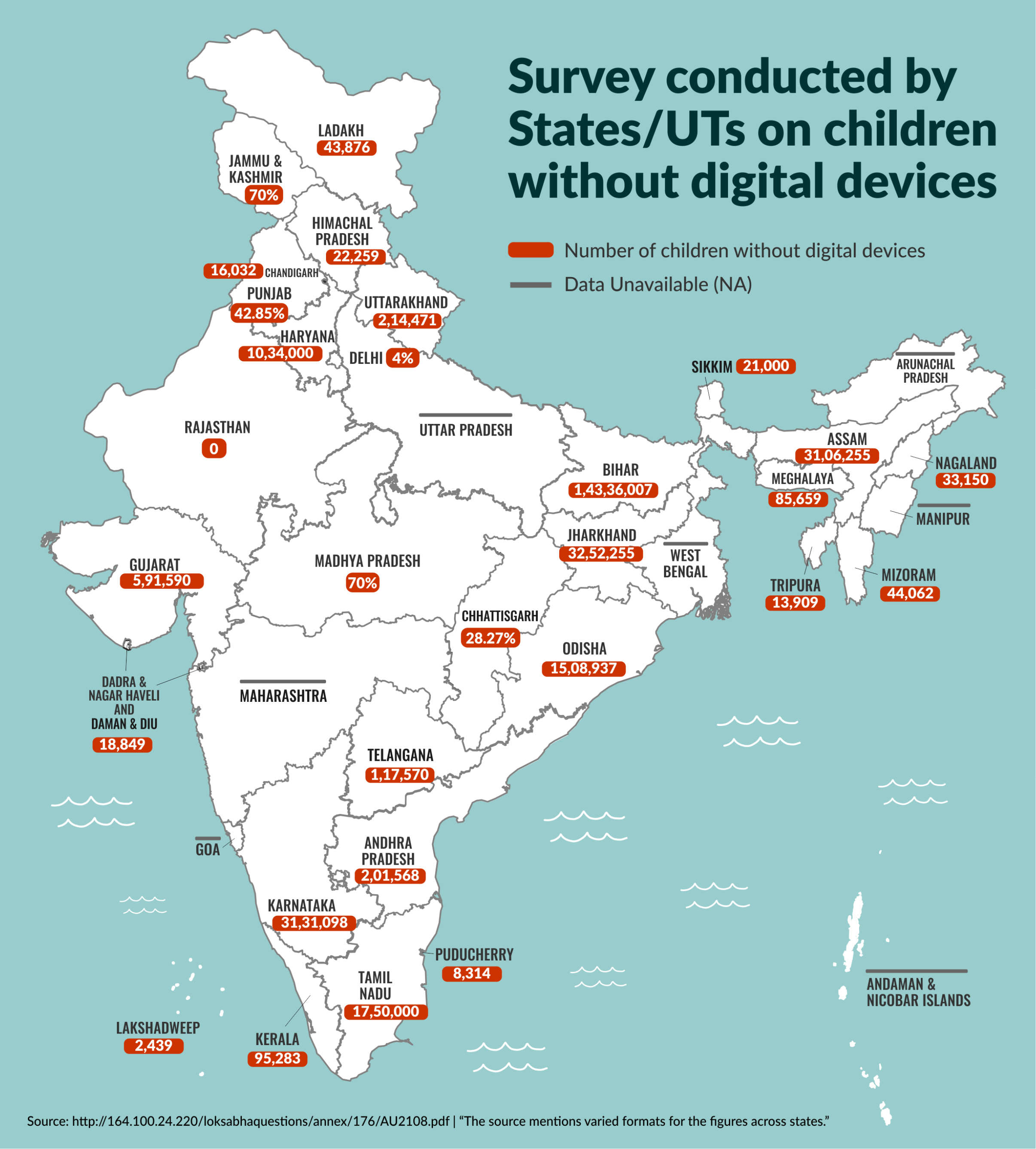

A field study undertaken by Centre for New Economics Studies, OP Jindal Global University in Lucknow, Pune, Bhopal, Jhansi, Katni focusing on daily wage workers, domestic workers and frontline health workers (ASHAs), revealed that 95 percent of respondents said their children had either dropped out of school or had stopped learning after the start of “remote learning”. Data by the Ministry of Education shared with the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Education, Women, Children, Youth and Sports highlighted that one crore children in Bihar and over 30 lakh children in both Jharkhand and Karnataka have no access to digital learning devices.

A substantive hidden cost of prolonged school closures is also the impact this would have on young girls across social fault-lines of class, caste, ethnicity. Experts have emphasised that in India, girls are worse affected than boys when a family faces huge setbacks and income losses, as millions of poor Indian families are currently facing lockdown and economic downturn. Families are more likely to push girl children to contribute to housework instead of studying during times of hardship. Additionally, even when they have access to educational resources, the lack of access to nutritious food and health supplies increases the chances of early marriage and risk of child labour.

A survey, conducted by Praxis India, a Delhi-based non-profit, which interviewed 290 adolescent girls, revealed that 36 percent of respondents said they were getting less food than before the lockdown (7 percent were even going without food on some days), 70 percent lacked access to sanitary pads, and 40 percent could not attend online classes. Additionally, adolescent girls usually get health supplements such as vitamins and iron-folic acid tablets and take-home ration (THR) through the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) or on Village Health and Nutrition Days. This had completely stopped during the lockdown.The impact of inadequate nutrition during adolescence can have serious consequences during the reproductive years of women.

ADVERSE IMPACT ON THE PHYSICAL AND MENTAL HEALTH OF CHILDREN

Apart from the impact on education, prolonged school closures have also had an impact on the health of school children.Around 12 crore school children from poor and marginalised communities used to rely on cooked mid-day meals in schools for nutrition. India’s mid-day meal programme is the largest in the world, and the prolonged closure of schools has put these children at severe risk of malnutrition. While the government implemented a Take Home Ration (THR) scheme, a study conducted by OXFAM India relieved that approximately 35 percent of children did not receive midday meals, and of the remaining 65 percent, only 8 percent received cooked meals while 53 percent received dry rations and 4 percent received the money in lieu.

It is estimated that nearly 70 percent of children, mostly from rural areas, urban slums, and other disadvantaged groups who are facing maximum learning and nutritional loss, due to the prolonged school closure. India is placed 94 amongst 107 countries on the Global Hunger Index (2020) — which is calculated on the basis of total undernourishment of the population, child stunting, wasting, and child mortality. A study conducted by ChildFund India, covering approximately 2,000 children from marginalised communities in the age group of 6-14, from 10 states suggest that around 73 percent of children said they were feeling sad and 8 percent were feeling anxious because they were not able to meet friends and teachers, were not able to access or/and understand online learning sessions, and were missing active face-to-face teaching-learning. A UNICEF India report in May 2020 also reported that parents of one-third of primary-school and half of the secondary-school children noted that their child’s mental and socio-emotional health had been compromised.

ARE CHILDREN MORE AT RISK OF COVID 19 IN THE THIRD WAVE?

State and central government authorities have expressed concerns about reopening schools in India as vaccination in India for those below 18 years of age still hasn’t been approved. For a country as populous as India, it is extremely difficult to ensure physical distancing in schools and educational institutions. Even when rules for social distancing are implemented, younger children, especially those in elementary schools, do not have the self-control or awareness that is necessary to follow such guidelines. There are fears that the reopening of schools will potentially lead to a spike in infections since it will lead to increased interactions between community members.

With the spread of the Delta variant in India, experts have warned that children could be at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 during the third wave. However, some studies also suggest that the third wave may not put children at any extra risk in comparison to adults. In fact, between August 1 and August 11, as per the Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) 543 children tested positive for COVID-19 in Bangalore, following which the Chief Minister convened an emergency meeting with experts regarding the effects of COVID-19 on children. However, no COVID-19 related death in the age group of 0-19 has been reported, and the infected children were mostly asymptomatic or had mild symptoms. However, some medical experts suggest that rising cases of COVID-19 in children in the third wave can be primarily because children have not been covered in the vaccination drive.

As of now, there is no data to ascertain whether COVID-19 has infected more children in the second wave compared to the first. Doctors confirm that they are seeing a larger number of COVID-19 cases amongst children, but cannot say with certainty if these are due to the earlier or new COVID-19 strain. The IAP (Indian Academy of Paediatrics), a body representing over 32,000 paediatricians in the country, has also confirmed that at least 90 percent of COVID-19 positive children will have very mild symptoms or none at all. However, treating younger patients who have COVID-19 has its own unique set of challenges. Children can not be subjected to Computerized Tomography (CT) scans which are used to check the severity of infection, due to radiation exposure. Additionally, the number of paediatric and neonatal ICUs in the country is far less than those for adults. Uttar Pradesh, one of the most populous states in the country, only has 78 newborn care units (each having 12 beds) that can be used to treat critically ill children. As of now, it seems unclear whether or not other strains of COVID-19 will affect children more seriously than the previous strains.

Even as schools have started opening in some states, there is an urgent need for the government to ensure that children and youth in danger of being left behind because of their background, identity, or ability do not drop out of school. As a part of the policy designed to reopen schools, the government must also account for policies and initiatives to ensure that those most susceptible to being left behind, such as girls, children from marginalised communities, and those from economically vulnerable households, also come back to schools when they reopen. The reopening of schools should be as much of a priority for the government as restarting economic activities. Hampering the education of children and young people will have a direct impact on the quality of the workforce which will enter the economy in the years to come, and prolonged school closures stand to hurt the country in the long run.