Tibet Work Forums (TWF) are large gatherings called every 5 to 10 years to discuss the policies of the Communist Party of China (CPC) for Tibet. They are regularly attended by the members of the powerful Politburo, including its Standing Committee, members of the CPC’s Central Committee, senior PLA generals, United Front Work Department officials and regional leaders.

One of the main decisions of the sixth gathering, presided over by President Xi Jinping, had been to develop tourism as the main activity on the plateau. Tibet thus became a large entertainment park, a thousand times larger than Disneyland, and brought nearly forty million Han tourists to the plateau in 2019.

While the previous TWFs completely escaped the Indian media, the Seventh TWF, held in Beijing on 28-29 August, got a wide coverage. It was a crucial event at a time when China is entangled in a tense face-off on the Indian frontiers, after Xi’s reckless moves in Ladakh. The Forum’s TV report lasted a record 14 minutes, mostly quoting Xi Jinping and showing the large ‘masked’ attendance, including the PLA’s Service Chiefs, highlighting the crucial significance of Tibet for the Communist Party.

It also came at a time when Beijing is celebrating the 70th anniversary of the so-called Liberation (read ‘invasion’) of Tibet, as well as the 55th anniversary of the creation of the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR), which has never really been autonomous.

To understand the TWF’s importance for India, it is necessary to remember Xi’s well-known theory about the ‘border areas’: “Governing border areas is the key for governing a country, and stabilising Tibet”. Since the month of May, we have understood better why China wants to stabilise and control its border: It needs to have a safe base for its military operations. The Sixth TWF had also decided on several poverty alleviation schemes, particularly the construction of hundreds of Xiaokang (‘moderately-well-off’) villages, some particularly close to the border with India.

Beijing’s unspoken rationale is that it is easier to control the ‘masses’ when they are sedentary and settled in well-connected villages (via wi-fi and surveillance cameras). It is a fact that today the whereabouts and actions of all the ‘resettled’ villagers can be controlled through their mobile phones and other surveillance gadgets. The development of these strategic villages is a crucial way to ‘govern the borders’ and has serious implications for India’s defence, as the demography of the border areas will be changed slowly by this.

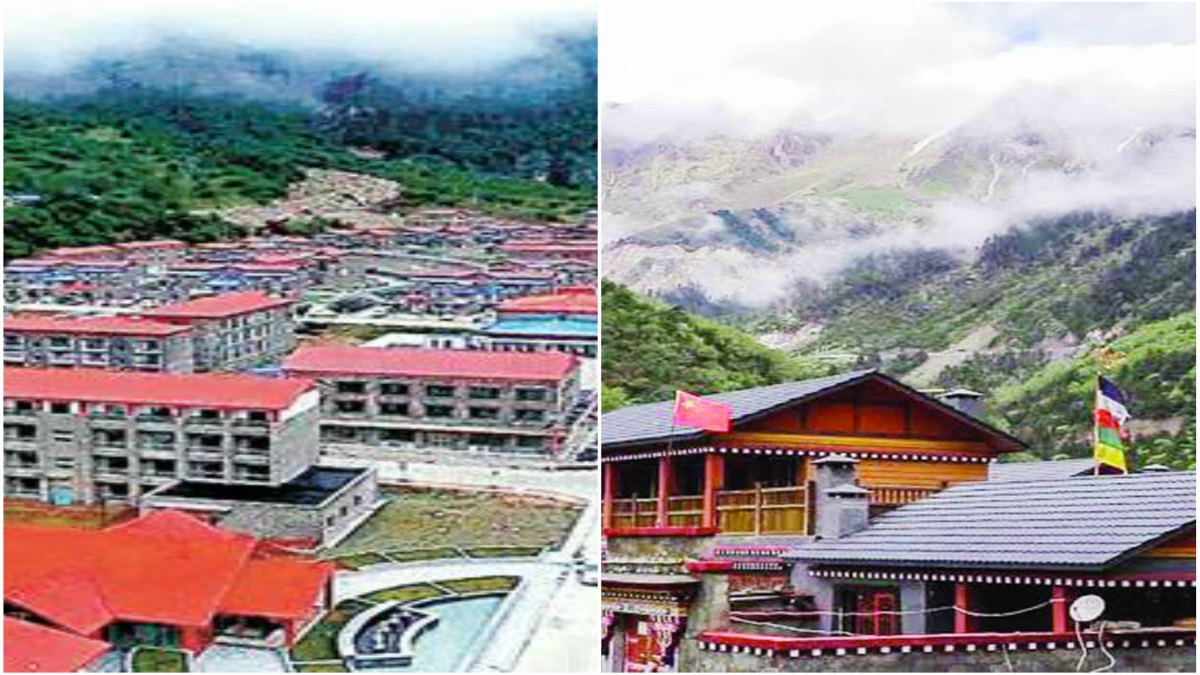

In October 2020, Xinhua announced that China has realised a historical feat: It had eliminated absolute poverty. Wu Yingjie, Communist Party of China’s Chief of Tibet, called the achievement a “major victory”, as by the end of 2019, Tibet had lifted 628,000 people out of poverty and delisted 74 county-level areas from the poverty list. Wu particularly cited the relocation of population in new ‘model’ villages, looking like ghettos, where the populations can be better controlled and where Han settlements can be brought in.

The figures are mind-boggling, according to Wu: “To date, the construction of 965 relocation sites [villages] has been completed and 266,000 people have moved into new houses. The relocation programmes were carried out entirely on a voluntary basis.” It is estimated that some 200 of these villages are located near the Indian border.

The fact that the ‘relocation’ has been voluntary is extremely difficult to believe; the pretext to transfer large populations, including nomads, is due to the rarified oxygen in the plateau. This is a strange argument when one knows that the Tibetans had lived for centuries in these conditions and have since long acclimatised. This, however, may apply to the new Han colonies ‘sharing’ these villages in what is called ‘ethnic mingling’.

YUME, XI’S MODEL VILLAGE

How did this start? Soon after the conclusion of the 19th Congress in October 2017, President Xi Jinping had written a letter to two young Tibetan herders, who had written to him introducing their village, Yume, north of Upper Subansiri district of Arunachal Pradesh.

Xinhua reported that Xi had “encouraged the herding family in Lhuntse County, in the Himalaya southwest China›s Tibet, to set down roots in the border area, safeguard the Chinese territory and develop their hometown.” Xi had acknowledged “the family’s efforts to safeguard the territory and thanked them for the loyalty and contributions they have made in the border area. Without the peace in the territory, there will be no peaceful lives for the millions of families,” he wrote.

LINKED TO INFRASTRUCTURE

Most of the time, the Xiaokang villages are linked to infrastructure development, particularly on India’s border. Hundreds of examples could be given. To cite one, the Pai-Metok (Pai-Mo) Highway, linking Nyingchi to Metok, north of Upper Siang district of Arunachal Pradesh, will be opened in July 2021.

On 12 October 2020, it was reported that the Huaneng Linzhi Hydropower Project Office (ominously, a dam company) was building the road in one of the most difficult terrains to effectively improve the current status of transportation from Nyingchi and Metok as well as the livelihood of the villages and towns along the route: “The project will be completed by the end of September 2022. After the completion of the Highway, the length of the road from Nyingchi City to Metok County will be shortened from 346 to 180 kilometres… and the driving time will be shortened from 11 hours to 4.5 hours.” The 67-km-long new highway will land a few km north of the McMahon line (Upper Siang district of Arunachal Pradesh). In strategic terms, it will be a game changer and greatly accelerate the relocation of populations on the border.

OTHER VILLAGES

These Xiaokang villages are located all along the Indian border from Rutok in Ngari Prefecture in the West to Rima (opposite Kibithu) in the Lohit valley in the East. A few model villages have been built on the Chinese side of the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Ladakh, others north of the McMahon Line in Tsona area.

A village which has received a lot of publicity recently is Jiru, located in Kampa Dzong (county), just north of the Sikkim border. An article in The People’s Daily stated: “The flower of national unity blooms on the border of the motherland.” It probably means that it will be inhabited by Han settlers. Jiru is “in the southwestern frontier of the motherland, with an average elevation of 5,050 metres, at a distance of 5 km from the China-India border, not far from seven passes [leading to India]. It is known as ‘the first village on the Sino-Indian border’,” says the Communist publication.

It is high time for Delhi to wake to the new reality and take effective measures to develop its own borders. Some steps have been taken in this direction; but can you believe that the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation Actof 1873 remains in force on some Indian borders?

Beijing’s unspoken rationale is that it is easier to control the ‘masses’ when they are sedentary and settled in well-connected villages (via wi-fi and surveillance cameras). It is a fact that today the whereabouts and actions of all the ‘resettled’ villagers can be controlled through their mobile phones and other surveillance gadgets.