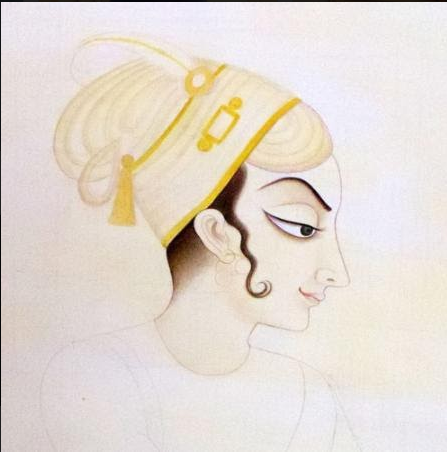

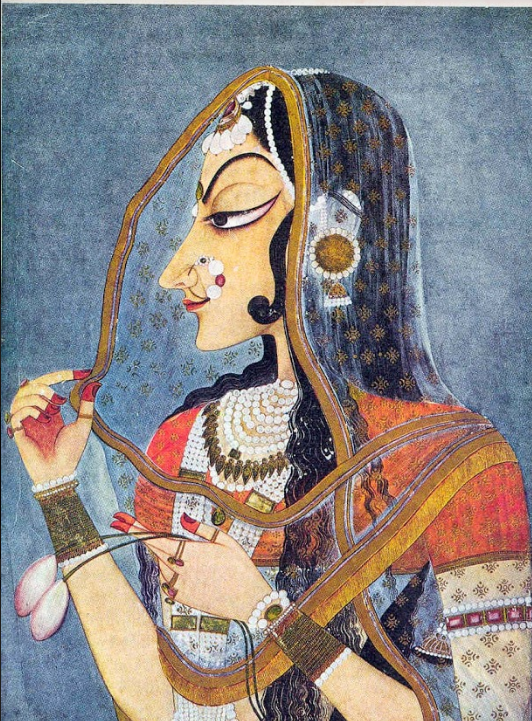

Of all the miniature schools of art, the Kishangarh School is the most unique and often acknowledged as the ‘finest of all Rajasthani miniatures’. It was founded in the 17th century by the then Kishangarh ruler, Maharaja Savant Singh (also called Nagari Das), a staunch Vaishnavite, and his chief court artist, the famed Nihal Chand, a follower of the Vallabha sect. Among the painter’s masterpieces, the “Kishangarh Radha” and Lord Krishna portrait (which was actually a portrait of the Maharaja) are the most iconic. His unique style is marked by elongated, aquiline features and exaggerated almond-shaped eyes. The famed Kishangarh Radha, often misquoted as “Bani Thani”, has also been turned into a stamp and is sometimes referred to as the Indian Mona Lisa.

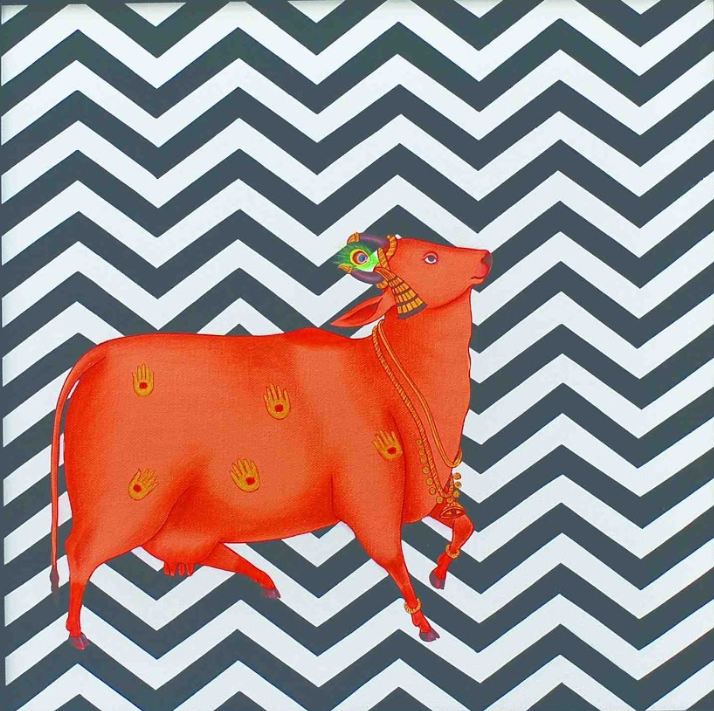

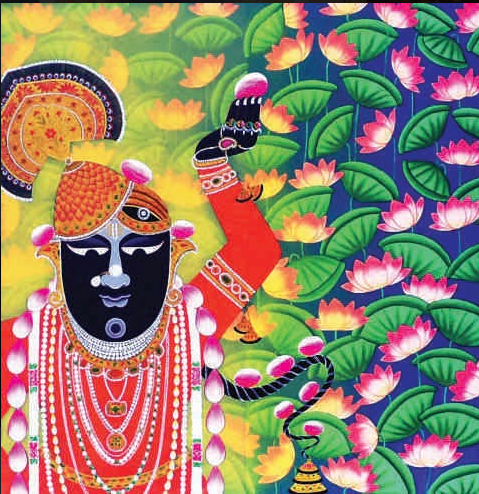

Cut to the 20th Century, the iconic style of the miniatures is still alive thanks to Princess Vaishnavi Kumari of Kishangarh. A postgraduate student of art from SOAS University, she is the founder of Studio Kishangarh which is aimed at reviving the glorious era of Nihal Chand. Vaishnavi had rekindled the world’s interest in the style about a decade ago when she recreated his masterpieces with a pop art element: almond-eyed Kishangarh cows, with their feet lined with alta, emerged on Andy Warholesque backgrounds, Krishna was put against a coat of bold red colour, and her love for chintz was turned into a watercolour painting.

The studio is situated at the foot of the Kishangarh Fort, with resident artists and a few surviving practitioners of the miniature art style. Vaishnavi credits her parents for her love for the arts, especially her father, Maharaja Brajraj Singh of Kishangarh, who is a “living encyclopaedia of miniature art”. “In our family all we ever talk about is art and history. I think one of my earliest memories as a child is being told stories about Hindu mythology, the Mahabharata and Ramayana. And because we grew up in our ancestral homes, we had a lot of art around us. I think when you see things around you on a daily basis and are exposed to something often, you tend to imbibe it on a subconscious level and that has helped me develop certain aesthetics and tastes over the years.”

Speaking about the iconic features of the Kishangarh school of miniatures, she says, “The “Bani Thani” is actually Radha and it’s a painting that idolizes beauty. It has very strong aesthetics, because of the strong features shown in the painting. However, that is not what Krishna paintings are all about, there’s a very deep undercurrent of Bhakti. My ancestors have been devout worshippers of Shrinath ji and have also written poems and books about the same. Thus, there has always been a very strong connection with Lord Krishna that we are still incorporating in our art.” “Our very successful divine cow series is something auspicious and yet an abstract depiction of god through the eyes of Bhakti. We also work a lot with peacock feathers, which is another emblem of Lord Krishna,” she explains about her current practice, mentioning her reverence for the Pichhwais which are used for worship and are now being recreated in her studio.

Remembering the glorious era of Nihal Chand, she shares, “He was a great artist. Before him was another artist called Bhavani Das who was trained in the Mughal court and worked with AzimUsh-Shan, who was the third son of the Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah. When Aurangzeb came to the throne in the 1700s, he stopped all his artistic pursuits. A lot of imperial artists went to sub-imperial centres like Pahadi centres or to different Rajput courts and developed their own styles there.”

Her husband, Kumar Saaheb Padmanabh Jadeja from the Gondol family of Kathiawar, Gujarat, speaks highly of her pursuit. “The legacy of Kishangarh is historic and I am proud of Vaishnavi for taking it forward,” he says.

However, Vaishnavi laments the decline in the quality of miniature art in recent times. She blames it on a lack of imagination and the tendency to produce copies. But her resolve to revive and maintain her legacy cannot be discouraged easily. “My underlying motivation in pursuing art history and design was always to identify the ways in which I could nurture it in my capacity as a patron in Kishangarh and preserve our artisans from the malady of stagnation and lack of inspiration,” she says.