Germany has had a special affinity for Indian mythology, literature and philosophy, which can be traced back to the country’s interest in Sanskrit. Since then, several German philosophers, scholars and even politicians have been inspired by works and ideas originating from India.

The German Empire, also called the Second Reich, was founded on 18 January 1871 in the wake of three short successful wars by the north German state of Prussia against Austria, Denmark and France. The unification of Germany (excluding Austria and the German-speaking areas of Switzerland) was achieved under the leadership of the Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. This new state replaced the German Confederation, a loose association of sovereign states and the highly decentralised Holy Roman Empire.

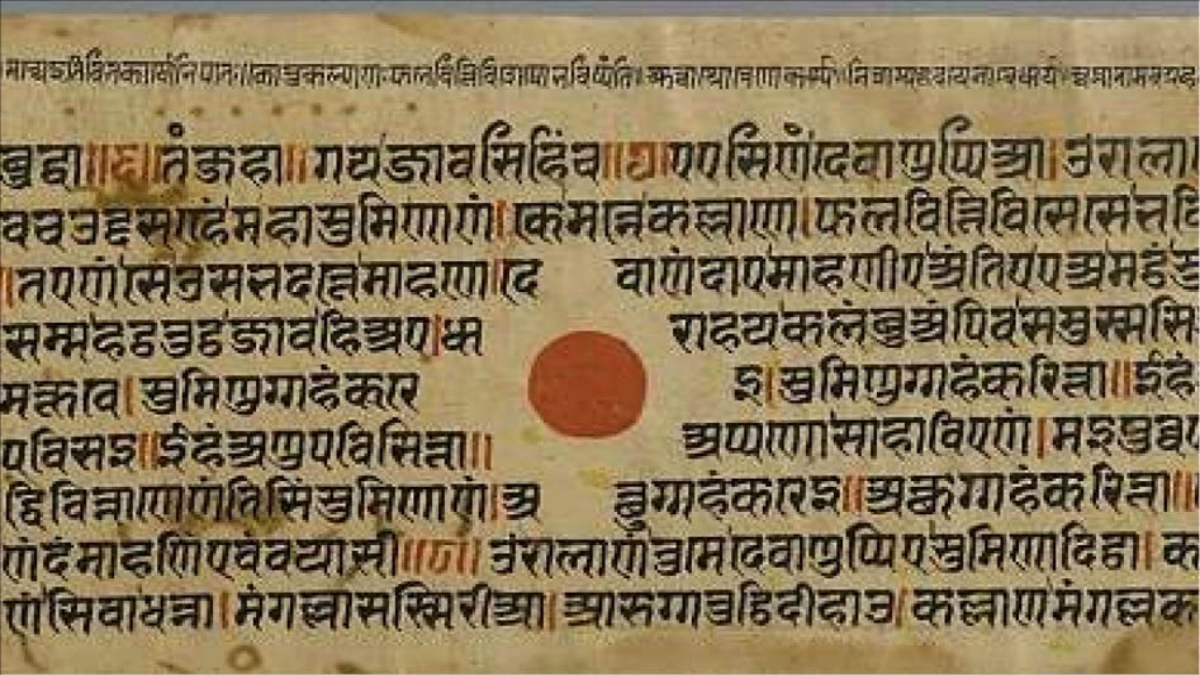

From the beginning, Germans showed great interest towards Sanskrit. The first German scholar of Sanskrit was Heinrich Roth (1620-1668). Then there was the poet, philosopher and Indologist, Friedrich Von Schlegel (1772-1829) who, in 1808, published an epoch-making book, Über die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier (On the Language and Wisdom of India). In the book, he advanced his ideas about religion and argued that a people originating from India were the founders of the first European civilisations. Schlegel compared Sanskrit with Latin, Greek, Persian and German, noting many similarities in vocabulary and grammar. He also said, “India is superior in everything — intellectually, religiously, even Greek heritage seems pale in comparison.” There was also Gottfried von Herder (1744-1803), a philosopher and theologist, who said: “‘Mankind’s origins can be traced to India where the human mind got the first shapes of wisdom and virtue.”

Max Muller (1823-1900), a German living in Britain, was the first to translate the Rig Veda. He also published The Sacred Books of the East, 49 volumes of which appeared between 1874 and 1884. His main aim was to convert Hindus to Christianity and believed that a thorough study of Hindu scriptures would help him to find the fault lines in what he considered a pagan religion. However, he became more and more impressed by what he found in the Vedas. “‘If I were asked under what sky the human mind has most fully developed some of its choicest gifts, has most deeply pondered over the greatest problems of life, and has found solutions of some of them which well deserve the attention even of those who have studied Plato and Kant, I should point to India. And if I were to ask myself from what literature we who have been nurtured almost exclusively on the thoughts of Greeks and Romans, and of the Semitic race, the Jewish, may draw the corrective which is most wanted in order to make our inner life more perfect, more comprehensive, more universal, in fact more truly human a life…again I should point to India,” he said.

In 1791, Kalidasa’s play Shakuntala made huge waves in Germany. Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe, German poet, dramatist, biologist, theoretical physicist and polymath, expressed his admiration for Shakuntala in the form of a poem. It was translated from German to English by E.B. Eastwick, and went: ‘’If you wish to see the young flowers of Spring and the ready to pluck fruits of Summer at once; or if you wish to see that object which pleases, hypnotises, delights and quenches you at once; or if you wish to see the earth and heaven in one look; I invoke the name of Shakuntala and all quests are answered at once.” In fact, so impressed was Goethe with Shakuntala that he had decided to learn Sanskrit. Goethe also became acquainted with Kalidasa’s poem, Meghduta (The Cloud Messenger). Kalidasa’s Vikramōrvaśīyam (Urvashi Won By Valour) as well as Malavikagnimitram were all translated to German between 1827 and 1856, while Kumara Sambhava (The Birth of the War God) was translated to German prose in 1913.

Shakuntala also wooed Johann Goffried Herder (1744- 1803), a philosopher and poet, who said about the text, “I cannot find a product of the human mind more pleasant than this, a real blossom of the Orient, the first and most beautiful of its kind.” He also said that India was a holy land he yearned for.

German Orientalist and Indologist Peter von Bohlen also translated The Three Sataks by Sanskrit writer Bhartrahari. Satakatraya (in Sanskrit) or Subhasita Trisati (in Telugu) is a collection of 300 poems on moral values. The first one, Niti Sataka, deals with ethics and morality, the second, Srngara Sataka, deals with man-woman relationships, and the third one, Vairagya Sataka deals with renunciation.

Philologist Franz Bopp (1791-1867) published the Analytical Comparison of the Sanskrit, Greek, Latin and Teutonic Languages, in which he extended to all parts of the grammar what he had done in his first book for the verb alone. He had previously published a critical edition, with a Latin translation and notes, of the story of Nala and Damayanti (London, 1819), the most beautiful episode of the Mahabharata. Other episodes of the Mahabharata, like Indralokagamanam, were also published.

Another German Indologist and professor of Philosophy at the University of Kiel, Paul Jakob Deussen (1845-1919), was strongly influenced by Arthur Schopenhauer. He was a friend of Friedrich Nietzsche and Swami Vivekananda, and even gave himself a Sanskrit name, Deva-Sena, as a mark of his admiration for Hinduism. He is one of the many distinguished Europeans who, often with lyrical admiration, participated in the scholarly Western discovery of Sanskrit and Hinduism that took place in Germany, France and England. It was when he attended a lecture by Professor Lassen expounding the Shakuntala that Deussen was fired up by Sanskrit and Hinduism. His first work was published in English as The Elements of Metaphysics in 1894. It was followed by the translations of The Sutra of the Vedanta in 1906, The Philosophy of the Upanishads, and the System of the Vedanta in 1912. After his visit to India in 1904, he also wrote a book in English, My Indian Reminiscences, which was published in 1912.

August Wilhelm Schlegel was a professor of Sanskrit in Continental Europe and produced a Latin translation of the Bhagavad Gita in 1823. It was the first Sanskrit book printed in Europe. This was the first of a self-financed, self-published series known as ‘The Indian Library’, which also included translations of the Ramayana and the Hitopadesha.

Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835) was a Prussian philosopher and diplomat, who, on reading the Bhagavad Gita, had said, “I read the poem for the first time today. I felt a sense of overwhelming gratitude to God for having let me be acquainted with this work. It must be the most sublime thing to be found in the world.” Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860), one of the greatest German philosophers and writers had also said, “In the whole world there is no study so beneficial and as elevating as that of the Upanishads. It has been the solace of my life and will be the solace of my death. They are the product of highest wisdom. Vedas are the most rewarding and the most elevating book which can be possible in the world.”

Werner Heisenberg (1901- 1976), Nobel Prize winner and co-founder of quantum physics, once articulated that “after the conversations about Indian philosophy, some of the ideas of quantum physics that had seemed crazy suddenly made much more sense”.

Heinrich Heine (1797-1856), German Romantic, poet, essayist and journalist, said: “The Portuguese, Dutch and the English have been for a long time, year after year, shipping home the treasures of India in their big vessels. We Germans have all along been left to watch it. Germany would do likewise but hers would be treasures of spiritual knowledge.”

This explains why Britain did not show the same interest in India›s great achievements going back thousands of years. It would be difficult to acknowledge anything positive of the country you have colonised. It would crush any moral justification of enslaving a nation. On the contrary, a narrative would have to be created to show ‹the natives› as uncivilised and backward. And so, a nation which had brilliant minds and had successfully solved so many unknowns in the field of science, mathematics, astronomy, economics, politics, architecture and a host of other fields, was reduced to being called a nation of snake charmers!

In fact, Sir Henry Maine, an influential Anglo-Indian scholar and a former Vice Chancellor of Calcutta University, who was also on the Viceroy›s council, pronounced a view that many Englishmen shared about the unification of Germany: A nation born of Sanskrit!

Sanskrit continues to be relevant in present-day Germany. The language has enjoyed a great revival in the country, with fourteen universities teaching Sanskrit, as opposed to just four in the UK. The Heidelberg University organises Sanskrit speaking courses in Australia, Europe, North America and even in India! This goes to say that both Germany and India can be custodians of Sanskrit!

As Danish historian Georg Brandes in his book, The Major Trends in Religion, had written, “It was not a surprise that there came a moment in German history when they — the Germans started to absorb and to utilise the intellectual achievements and the culture of India. It is because this Germany — great, dark and rich in dreams and thoughts — is in reality modern India. Nowhere else in the world history has metaphysics bereft of any empirical research achieved such a high level of development as in ancient India and in modern Germany.”

Unfortunately, Hitler too had a connection with India. Hitler usurped the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist religious symbol, known as the swastika, in both Sanskrit and German. Hitler›s senior commander, Heinrich Himmler, was also known to carry the Bhagavad Gita in his pocket. He obviously completely misunderstood the core message of the Hindu holy book. Himmler also liked Hermann Hesse’s novel, Siddhartha greatly, whose story is about the spiritual journey of selfdiscovery of a man named Siddhartha during the time of the Gautama Buddha.

In a surprising discovery, a 40,000-year-old “ManLion” sculpture was also found in Germany, reminiscent of the legend of Lord Narasimha, who had appeared to kill the demon, Hiranyakashipu. It was discovered in 1939 in the Hohlenstein-Stad, a German cave. The ivory sculpture of a half-man, half-lion is considered the oldest piece of art ever found. The German name for it is Löwenmensch, meaning “lionhuman’’. However, it was not until 2009 that all the pieces were put together. A computer simulation produced the half-man, halflion image. Could it be that whoever made this sculpture was a devotee of Lord Narasimha? By a strange coincidence, ISKCON and the Hare Krishna movement have a temple and a farming community in the Black Forest area of Germany, called Simhachalan. It is the only temple in Europe which has Lord Narsimha as the main deity of worship. The temple is about 200 km from the site where the “Man-Lion” sculpture had been found!

More than 40,000 years later, Lord Narsimha appears again!

Nitin Mehta is the founder of Indian Cultural Centre, London