In the last few pieces, this author had undertaken a discussion on constitutional morality, its nexus with public morality, and the nature and scope of intervention permitted by the Indian Constitution to the State and the Judiciary respectively in relation to public morality. This also led to a discussion on whether the Judiciary forms part of the State within the meaning of Article 12 of the Constitution, and whether the remedy and right under Article 32 is available in respect of the Judiciary. The sum and substance of these discussions is that under the framework of the Indian Constitution, it is the State, meaning thereby the Executive and the Legislature but not the Judiciary, which has the power to invoke public morality within reasonable bounds for the purposes of placing reasonable restrictions on fundamental rights guaranteed by Part III of the Constitution. The Judiciary’s role is limited to examining the constitutional validity of the claim made by the State that the latter’s action is in the interest of or furthers public morality. That said, what are the parameters that must be applied to such an examination? In other words, how does the State demonstrate that its action represents public morality? What kind of exercise must the State undertake, if at all required by the Constitution, to assess public morality in relation to a given right? Or does the Constitution grant elected representatives the unfettered right as parens patriae i.e. parent of the nation, to speak on behalf of their constituents on every issue merely because they have been elected? Can members of the State form an opinion on public morality in relation to a given issue or topic without consulting members of the society to marshal some form of concrete evidence to base their positions on? Critically, in the context of a diverse society such as Bharat, how can the State hope to do justice to varying and often conflicting positions on public morality?

This perhaps requires us to dig deeper to address something more fundamental, namely the very basis for providing public morality as one of the constitutionally permitted fetters on individual rights. If the Constitution indeed celebrates individual rights and dignity as “a shining star in the constellation of fundamental rights”, how does one explain the constitutionally permitted eclipsing of this shining star by the State on grounds of preserving public morality? Does this not point to the fact that the Constitution, notwithstanding its recognition of and commitment to fundamental individual freedoms and dignity, also recognizes the big picture of the nature of “society”?

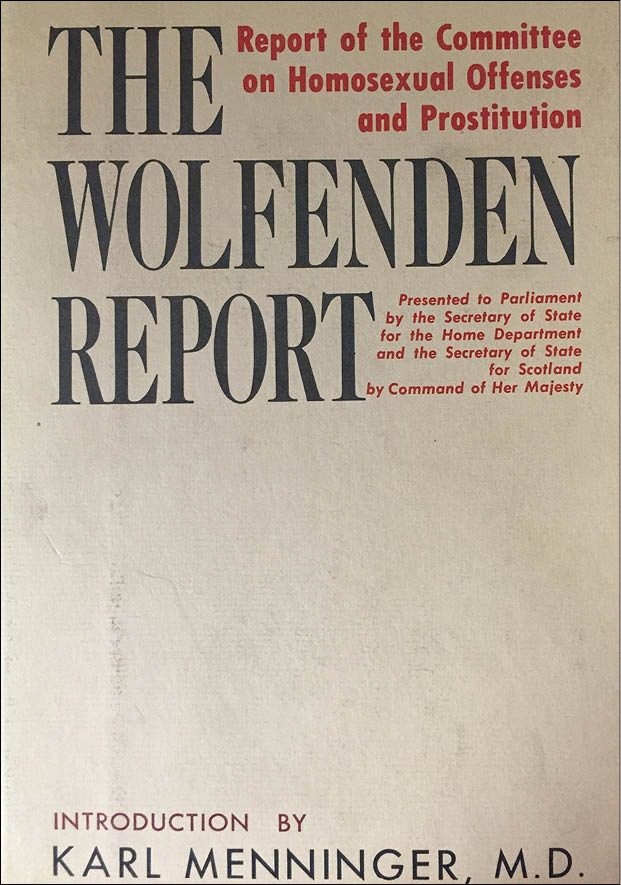

Students of English jurisprudence are familiar with the famous Devlin-Hart debate on the nexus between public morality and law which had Lord Patrick Devlin, a British Judge and legal philosopher on the one side, and Professor Herbert Lionel Adolphus Hart, a Professor of Jurisprudence at Oxford University on the other. The debate was triggered by the Report of the Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution published in 1957 by Sir John Wolfendon who recommended decriminalization of homosexuality in the UK after a string of high-profile convictions. While Devlin opposed the Wolfendon Report’s recommendations, Professor Hart supported them. Their exchanges through publications on the nexus between public morality and the law is a must-read, even if their positions are deemed to be reflective only of the worldview of the civilization they come from, and may or may not be consistent with Indic civilizational ethos

In his lecture against the Wolfendon Report and later in his book The Enforcement of Morals, Devlin argued that society means a community and communion of shared views on morals and ethics, and that the State’s power to limit individual freedom on grounds of public morality comes alive when individual conduct threatens society’s constitutive morality i.e. shared moral bonds which hold the society together. Hart, who supported the Report, too wrote in 1971 as follows:

“A collection of individuals is not a society; what makes them into a society is among others things a shared or public morality. This is as necessary to its existence as an organized government. So society may use the law to preserve its morality like anything else essential to it.”

However, the point where Hart differed from Devlin is the area of private life, where Hart believed that the scope for the use of public morality was limited. Does this mean that the scope of use of public morality by the State as the basis for limiting individual freedoms is limited to public spaces? What is the position of the Indian civilization and the Constitution on the spaces and contexts in which public morality may be used as a legitimate restriction on individual rights? What constitutes public morality within the framework of the Indic civilizational worldview and what are its sources? These and other such questions will be addressed in the next few pieces.

J. Sai Deepak is an Advocate practising as an arguing counsel before the Supreme Court of India and the High Court of Delhi.